Lying in bed for two months with a broken neck, 18-year-old Ricardo Izecson dos Santos Leite made a list of 10 goals. Nevermind the fact that he was uncertain to ever play again after fracturing his sixth vertebra at the bottom of a waterslide.

And forget cautious optimism. These were audacious dreams even for a boy raised on the soccer mania of Brazil—especially one who had needed a medical program to spur his stunted growth and who was yet to crack the starting lineup of the junior squad of São Paulo Football Club. The list began with “Return to soccer” and scaled upward to finish with “Compete in the World Cup” and “Transfer to a big club in Italy or Germany.”

In January 2001, about two weeks after returning to soccer, he was called up to São Paulo’s professional team. On March 7, with 10 minutes remaining, he was subbed into the finals of the prestigious Rio-São Paulo Tournament. São Paulo trailed Botafogo 1-0 when the midfielder received a high, looping pass, flipped it behind the back of a defender and fired a low shot beneath the diving goalkeeper. Two minutes later he netted another low rocket to clinch the championship as TV announcers shouted “Goooooooooooooooal!”

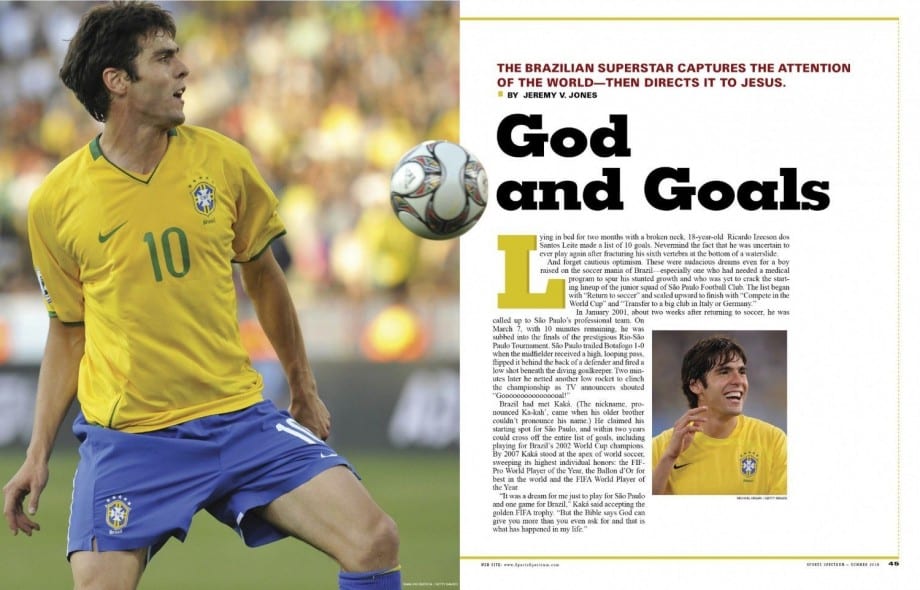

Brazil had met Kaká. (The nickname, pronounced Ka-kah’, came when his older brother couldn’t pronounce his name.) He claimed his starting spot for São Paulo, and within two years could cross off the entire list of goals, including playing for Brazil’s 2002 World Cup champions. By 2007 Kaká stood at the apex of world soccer, sweeping its highest individual honors: the FIFPro World Player of the Year, the Ballon d’Or for best in the world and the FIFA World Player of the Year.

“It was a dream for me just to play for São Paulo and one game for Brazil,” Kaká said accepting the golden FIFA trophy. “But the Bible says God can give you more than you even ask for and that is what has happened in my life.”

Faith and Family

Kaká’s star shot into the stratosphere in soccer-mad Brazil following his breakout game. The press couldn’t get enough of him, and he was an instant heartthrob. He couldn’t go out in public without being mobbed. At first Kaká’s mother answered the 50 letters a day from female admirers, but the flood of attention quickly became too much.

After the initial shock, Kaká developed a warm accessibility with the press and fans, but he avoided the limelight and temptations of the nightclubs and paparazzi scene. As had always been the case, his family and faith were his anchor.

Many people think that I became a Christian after the accident, but that is not true,” Kaká says. “My parents always taught me the Bible and its values, and also about Jesus Christ and faith.”

Being baptized at 12 was an important milestone for Kaká and one that had a profound effect on his young spiritual life. “Little by little, I stopped simply hearing people talk about the Jesus my parents taught me,” he says. “There came a time when I wanted to live my own experiences with God.”

Europe Bound

There’s a common saying about soccer: “England invented it. The Brazilians perfected it.” The Brazilian game is generally an artful, rhythmic flow marked by skillful dribbling and unexpected passing. The nation brought joga bonita, the beautiful game, to the world and holds more World Cup championships, five, than any other country.

But Europe is the epicenter of professional soccer. The big money of each nation’s pro leagues draws the world’s top talent, and the continent-wide UEFA Champions League ensures the highest stakes of competition and talent. So it was no surprise in 2003 when the 21-year-old Kaká went to play for AC Milan in Italy’s Serie A.

European soccer is generally considered more physical and tactical than the South American game, but the 6-foot, 1-inch, 180-pound Kaká adapted instantly. His first season he earned a starting role, scored 10 goals and helped Milan win the Scudetto, the Serie A championship. He was named the league Player of the Year.

“[Kaká ] has the technique of a Brazilian and the physical qualities of a European,” Vanderlei Luxemburgo, former Brazilian national team coach, told FIFA.com. “He is the standard-bearer of the modern game.”

By 2005, Kaká and Milan reached the Champions League final where they squandered a 3-0 halftime lead and lost to England’s Liverpool in penalty kicks. The Rossoneri returned in 2007, however, to win the Champions League in a rematch against Liverpool. Kaká ’s string of best-in-the-world awards followed, and he was named to the Time 100 list of the world’s most influential people.

After turning down a transfer offer of $151 million from England’s Manchester City, Kaká and Milan agreed to a $100 million deal with Spain’s Real Madrid in 2009.

The record-breaking deal was eclipsed within weeks when Real Madrid paid $131 million to sign Cristiano Ronaldo. Ultimately the team spent $350 million on international stars in order to reclaim domestic and European dominance.

Kaká struggled with some nagging injuries, and the entire team didn’t immediately gel. Expectations on Los Blancos were incredibly high, and fans cried for the firing of coach Manuel Pellegrini when they lost to France’s Lyon in the first knockout round of the Champions League. However, Real Madrid finished second to Barcelona for the Spanish title.

Radical

Kaká ’s accomplishments on the field obviously brought him worldwide prominence, but his personal reputation has also drawn widespread attention as a novelty among international sports stars. Pick an international soccer—or professional athlete—stereotype and Kaká contradicts it.

He’s Brazilian, so he grew up in poverty playing with a homemade ball? Both of Kaká ’s parents were well-educated professionals who raised the family in an affluent area of São Paulo, and Kaká attended São Paulo FC’s soccer academy.

He must play with lots of flashy dribbling and Brazilian flair? While his fundamental ball skills are extraordinary, Kaká ’s style is strong, yet elegant and efficient. “He will always try to go vertically rather than horizontally,” AC Milan coach Carlo Ancelotti told The Observer, a British newspaper based in London. “He will never take the extra, unnecessary touch.”

But what about off the field—another carousing playboy like so many international stars? Hardly. Kaká and his wife, Caroline, famously married as virgins in 2005 and have talked about it openly in the press. “It was one of the greatest challenges in my life because we made a choice which wasn’t easy,” Kaká says. “We spent a lot of time praying and walking closely with Jesus and the Holy Spirit. It was a great challenge, but it was really good to have waited. Sex is a great blessing from God for the pleasure of both husband and wife after marriage, and it is not the trivial or casual thing it has become nowadays.”

Surely he’s self-centered and materialistic? Kaká’s generous giving to his home church in Brazil is widely known. He has also served as a United Nations Ambassador Against Hunger since 2004 and hopes to be a pastor after he retires from soccer. “Kaká never changed,” says Marcelo Saragosa, his best friend since childhood and player for Chivas USA. “He is always the simple person as when I met him 10 or 12 years ago.”

Most media have shown respect for Kaká’s faith and praised his sportsmanship. His consistency and graciousness matched with his stellar play make it difficult to do otherwise. Yet when some have suggested that his lifestyle is boring, Kaká has countered that it is radical to follow Christ.

As Kaká continues to pursue his new goals—another World Cup title, European championship and best player in the world honors—he leaves little doubt that he is all about Jesus.

“Today, I have my ministry through sports, but I play because I have a God-given gift,” he says. “I play because He has perfected the gift He gave me in my life. Jesus said ‘without me, you can do nothing’ and I believe this.”

By Jeremy V. Jones

This story was published in the Summer 2010 issue of Sports Spectrum.