It is December 8.

Eleven days before Reggie White’s birthday.

Eighteen days before the 11th anniversary of his death.

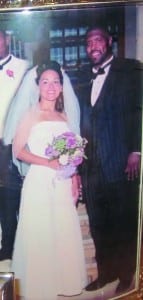

Less than a month away from what would have been his 31st wedding anniversary with his wife, Sara.

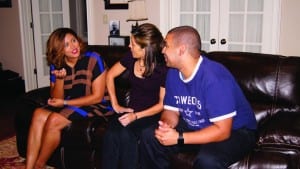

Sara, Jeremy and Jecolia (her and Reggie’s two children), are sitting on a living room couch in Sara’s Mooresville, North Carolina, home—eight miles away from Reggie’s gravesite. All around there are memories. Photo collages hanging on the walls. Display cabinets with wedding photos. A wooden cabinet nearby with ancient Torah scrolls from Israel inside. Plastered on a wall nearby: Life is not measured by the number of breaths we take, but by the moments that take our breath away.

As the three of them sit together and reflect on the last decade—one that was without their family’s leader and cornerstone, a husband and father who was as widely respected off the field as he was on the field, which is saying something considering he was arguably the best defensive end in NFL history—there are moments of seriousness, sure. After all, what they experienced was traumatic, blindsided by the course of death, when Sara awoke at 7 a.m., the day after Christmas 2004, to Reggie coughing and choking. Reggie died later that day—from a cardiac arrhythmia triggered by sarcoidosis, a disease where nodules form in the lungs, liver, lymph glands and salivary glands. The holidays, though the Whites do not celebrate Christmas, are still undoubtedly poignant.

Overall, however, the mood in this room is joyful. They laugh a lot whenever they reminisce about Reggie. They laugh a lot, in general, whenever they are together. Sara is sitting in the middle of Jecolia, 27, and Jeremy, 29. For once, Sara is the quiet one. And Sara is never the quiet one. But sitting there on the couch between them, she can hardly get a word in between their playful bickering, Jeremy’s random rants, and Jecolia’s attempts to keep Jeremy on prompt. Jecolia knows better. Her older brother cannot be tamed. Perhaps none of them can be tamed when they are together. Watching the Whites interact is like watching a sitcom unfold. Hilarious havoc.

The interview with the Whites was supposed to last only five or ten minutes, simply to gather some video footage for the story. It has already lasted over an hour and a half. Maybe they have forgotten they are being recorded.

Today, Sara and her children’s lives are intertwined on a number of levels. Jecolia recently moved into her mother’s basement to save money. Jeremy and his wife live down the street. Sara owns her own real estate business in Charlotte, North Carolina, called CLT Residential, and Jecolia is one of her agents. Both Jecolia and Jeremy teach in the Charlotte area. Jecolia: at a local high school. Jeremy: kindergarten.

They are all together on a regular basis.

It might be easy to think that this is the way it has always been with them. And for a time, it was. Sara says that in her and Reggie’s 19 years of marriage, there were only 18 days when neither of them saw their children. Sara knows that might sound crazy, but she and Reggie felt most whole, most fulfilled, when they were with their children.

Sara and Reggie always told one another that once they became empty nesters, when both Jeremy and Jecolia went off to college, they were going to purchase an RV. On one side, maybe they would paint the words, “JEREMY’S PARENTS”; on the other side, “JECOLIA’S PARENTS”. Then they would travel back and forth between their universities, embarrassing their children.

When Reggie died, all of that changed. Jeremy was a freshman in college. Jecolia was a junior in high school. Sara did indeed become an empty nester two years later. But she never did purchase an RV. There was no one to ride beside her.

Laughter floods the room, as it has been all evening.

Sara’s pet parrot keeps ringing its bell and occasionally squawking in the background.

The question is asked: If Reggie was here today, is there something you want to tell him?

The mood changes, but only for a moment.

Then Sara smiles. Humor is welcomed back into the conversation.

“When there is a new earth and we come back with new bodies, I will tell him: ‘I cannot believe you left me with a 16-year-old daughter and 18-year-old son! Really?’” Sara laughs.

Her children join in.

“I know what I would say,” Jeremy says, before telling a random story about how he found value in journaling.

“Jeremy,” Jecolia says, “stay focused.”

“I’m mad,” Jeremy eventually says, getting to his point, “because he was supposed to see how Marvel Cinematic Universe is taking over, okay? Every single time I see a superhero movie, I’m like, ‘You left at the cusp! When you left, two years later, Batman Begins comes out. You would have flipped out! Every superhero movie, I’m telling you. Except Green Lantern. Green Lantern was terrible. Don’t go see Green Lantern. (Jeremy goes on a miniature rant about Green Lantern.) Anyway, going back, you had to leave on the cusp of superhero movies. Was Ironman not the best superhero movie at the time besides Batman?’ The kid in him would have flipped out. I love my wife, but she doesn’t like superhero movies, so I go by myself. But if he was here, I would go with him.”

Jecolia and Jeremy then talk about how impossible it is to watch superhero movies with their mother.

“She talks too much,” Jecolia says.

“She asks too many questions,” Jeremy says.

“Or she tries to guess what is going to happen next,” Jecolia says.

Jeremy then talks about how much Reggie loved comic books.

And about how much Reggie loved Star Wars.

“How much can you explain this?” Jecolia says.

“He was a geek,” Jeremy says. “And nobody knows he was a geek. He’s the one person I know who would appreciate all of this so much…We could have talked about adult things, like the psychology of Joker…”

“Your point has been so proved,” Jecolia says sassily.

“And here’s the other thing,” Jeremy says, “He would have loved how many black superheroes have become popular.”

“Well, they’re making black people into superheroes on the screen,” Jecolia laughs. “They’re actually not black superheroes.”

Jecolia and Jeremy then start to argue about The Falcon.

Sara speaks up, “This is what Jecolia would say to Dad: ‘Look at what you left me with,’” and then points at Jeremy.

“Here’s what I would like to say to him, okay?” Jecolia says. “‘One, you shouldn’t have talked about all the things you were going to do once I graduated college, because then maybe I would have started career planning earlier. Thanks for that. Blaming you.’”

Jeremy and Sara laugh.

“And then, two, ‘Thank you for always talking about how you were going to intimidate my future boyfriends, because that has resulted in not really having any,’” she jokes. “Also, it’s kind of hard in the dating world when your dad was this real famous, big football player. It’s kind of intimidating for everybody. So my dating life is not good. ‘Blaming you.’”

Sara was always the strong one. She had to be. She was married to Reggie White, the best defensive end of all time, and one of the most vocal Christian athletes of all time. The Tim Tebow of his day. Except also a 13-time Pro Bowler, two-time NFL Defensive Player of the Year, Super Bowl XXXI champion and Pro Football Hall of Famer.

When the Philadelphia Eagles signed Reggie, Sara was only 21 years old. By the time she was 22, she and Reggie were already providing marital counseling for couples. Because of Reggie’s sudden stardom, renowned leadership and the platform he had with his faith, people flocked to the Whites for counsel and advice and comfort—first in Philadelphia (1985-1992), then in Green Bay when he played for the Packers (1993-1998), then in Charlotte when he played for the Panthers (2000). Reggie and Sara loved ministering together. It never really was about football for the Whites. It was always about people. Relationships. Brokenness and redemption. When Sara felt weak, she had Reggie. When Reggie felt weak, he had Sara. They could lean on one another when they were tired. They could breathe encouragement into one another when they were discouraged. Sara felt the freedom to feel weak around one person, and that was Reggie.

“I’m the type of person who is like, ‘I’ll worry about you, but don’t you worry about me; I’ll come and help you, but don’t come and help me,’” Sara says.

When Sara was diagnosed with MS (multiple sclerosis, an unpredictable and often disabling disease of the central nervous system), one year before Reggie died, she didn’t even tell her parents about her disease for five long years. In fact, the only reason why she ended up telling them was because they heard about it from someone else.

“What could they do?” Sara says. “I didn’t want them to worry about me.”

When Reggie died, her crutch to lean on was gone; the person breathing life into her whenever she felt discouraged was no longer around. Still, she felt that she needed to keep up the charade. She needed to be strong for her children. For family. For friends.

Naturally trying to cope, she dove into something that would keep her busy. She plunged into real estate, a profession she had always wanted to pursue. She worked herself into a frenzy. Though she enjoyed what she did, she admits that work became her crutch. Work is always a wobbly crutch.

“My sister always told me, ‘You take on too much,’” Sara says. “I didn’t get counseling. I really felt like I did that because I didn’t want to seem weak, like I needed to see a therapist. People think that to see a therapist, you must be weak, so what’s wrong with you? That was the stigma.”

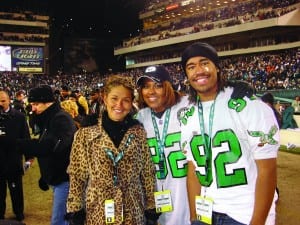

Sara, Jeremy and Jecolia are trying on (and fighting over) some of Reggie’s hats—an Eagles cap from the 80s; a Packers cap from the early 90s; a Panthers cap from the year 2000; a Hall of Fame cap from his 2006 induction, two years after he died; and a retro Cowboys hat. Reggie never played for the Cowboys, but Jeremy, for whatever reason, is a Cowboys fan. At his father’s Hall of Fame induction, several Eagles fans spotted him purchasing an armful of Cowboys gear. They confronted him about it, too, because that’s what Eagles fans do.

Aren’t you Reggie White’s son?

Jeremy thinks that when his father passed away, he put a curse on the Cowboys since, for some reason, his only son is a Cowboys fan.

Now Jeremy is standing on their coffee table, wearing his father’s Cowboys hat, doing an impersonation of one of his teaching heroes, Ron Clark, an enthusiastic educator who opened the Ron Clark Academy in Atlanta, Georgia, where Jeremy visited last week. Jecolia and Sara are rolling their eyes. Apparently he talks about Ron Clark a lot. Still, they’re entertained. Jeremy is passionate about teaching, and he seems to be good at impersonating Ron Clark.

For the first time in Sara, Jeremy and Jecolia’s life, not only were the three of them without Reggie, but they were also without one another on a daily basis.

Jeremy’s individual journey begins at the root of worry. He was tempted to forgo his return to Elon University after his father passed, to care for his mother and sister back home, to be the man of the house, to fill the void. They assured him they would be okay. He returned to Elon somewhat plagued with guilt for not being back in Charlotte with them.

“I used to worry about everything I couldn’t control,” Jeremy says. “I think after Dad passed away, the first thing that set me free from that was that I stopped putting pressure on myself about what I thought someone who cared about me wanted me to do. I always gave myself the affirmation: You need to do exactly what it is that you are doing, and that is what everyone who loves you would want you to do.”

After graduating, he went even further away—to Japan. There, he met his future wife. He continued to discover his passion for teaching and education.

Upon graduating from high school, Jecolia went away, too. Though she had always felt like she might work for her dad in some way, helping him in some of his business endeavors that he always talked about, now she felt as if she was starting from ground zero. What was her passion? What was she to do with the rest of her life now that her dad was gone?

First, she went to the University of North Carolina; then, to her dad’s alma mater, the University of Tennessee, where she was pursuing her Master’s in psychology. She also worked for the football program, and her dad’s spirit was all around. This was comforting.

At Tennessee, she even grew close to one of her father’s good friends: his former college teammate, Harry Galbreath. Galbreath had given Jecolia her first Barbie doll when she was four years old. Now he worked at Tennessee. In 2010, however, Galbreath died, too—from a blood clot when he was in Mobile, Alabama.

So little time. So much loss. Old wounds…re-punctured.

It’s hard to say whether Jecolia’s time at Tennessee helped her deal with pain and move through grief or caused more pain to well up within her. What was most beneficial for her at Tennessee, however, was her education. She learned all about mental health and psychology and counseling. She would often call her mother and give her advice. Jecolia bluntly told Sara that she needed to sit down with a counselor.

“I think Jecolia found a good counselor when she was at Tennessee,” Sara says. “And I know that really helped her, and through her being helped, it helped me.”

Ironically, when Sara was pregnant with Jecolia two decades before, she was working in a psychiatric ward at Ancora Hospital in New Jersey. Now, her own daughter seemed to be saving her with psychology.

“I’ve always been worried about my mom, which she doesn’t like, but it’s just natural,” Jecolia says. “It’s just, I don’t know, my mom is very strong, but my mom’s way of coping is just to keep moving—and I think it catches up with you.”

Because of Jecolia, who Sara says has become “closer than a sister” over the years, Sara eventually sat down with a counselor for the first time.

“The first time I went to counseling, we were just talking about loss, and I just broke down and said, ‘I’m tired of being the strong one,’” Sara says. “And I just cried. I paid her to hear me cry. It was all just overwhelming, because you’re thinking about…just crying and thinking I shouldn’t have taken this all on.”

What advice would you give to someone who is dealing with loss?

Jecolia begins: “You have to go through it. You can’t skip it. You can’t put it off. And you should feel it, because when you care about someone, it hurts when they are gone…I don’t know if it’s our society or what, but as a whole, we aren’t really prepared for death. We are scared of it…And we also don’t really like to show our emotions. But there are appropriate responses to sad things.”

Jeremy continues: “My friend once sent me a text that said, ‘My grandmother died; what do I do?’ I said, ‘Cry. And don’t let anybody tell you when the time is that you are not supposed to cry.’…You cannot tell somebody how long it’s supposed to be or how long you are supposed to grieve…Sometimes you are expecting it, and sometimes it hits you like a ton of bricks. People think, ‘Well, you are supposed to get back to normal.’ Well, this is my new normal now.”

Sara concludes: “I think focusing on the happy memories can help you get through it. We cried and we laughed…Don’t skip it. Remember it. And talk about it. I think part of healing is talking.”

And maybe healing takes place, in a new and different way, each time the three of them get together. Maybe healing is taking place right now as they talk.

As Sara and Jeremy and Jecolia each ventured through the valley of grief in each of their own different ways over the last decade, Reggie would perhaps be most proud of how each of them has continued to discover their spirituality. It was one of the foundational principles he left with them: the beauty of discovery. The freedom of exploring the incomprehensible.

Reggie White’s spirituality the final five years of his life has been speculated in the media for years. Did he renounce his Christianity? Did he become a Jew? Why did he and his family stop celebrating holidays like Christmas?

According to his family, Reggie White never stopped following Jesus; he just went deeper into the woods on the trail of knowledge than most choose to venture down in their lifetime. It was not uncommon for him to spend eight hours or more a day studying the Hebrew language, scouring through the Old Testament, challenging all his preconditions about Christianity, questioning its traditions. Reggie studied. His family followed.

“We decided not to call ourselves ‘Christians’ because ‘Christians’ was in a box,” Sara says. “But being a believer is not in a box because it helped us continue to learn what we were believing in. So now we are looking at the Bible from a different perspective, from a historical background, instead of how we had read and learned since I was 16 or 17, and since he was 16 or 17. And we studied for ourselves.”

Sure, maybe Reggie had more questions than he had answers. Maybe sometimes he took things too far. Maybe he sometimes took the Old Testament too literally. Like the time he asked Sara to consider covering her head and arms and legs, like the Israelite women of the Old Testament. Sara told him she would pray about it, then told him that she wouldn’t unless she lived in a culture that did. “You’re right,” Reggie told her. Then he apologized.

“That’s why I love you,” Sara told him, “because you want to closely follow God’s Word.”

It’s for that same reason the Whites stopped celebrating Christmas. Not because they wanted to downplay the birth of Christ, but because they believed the holiday had pagan roots. Sara says it is historically proven Christ was born in the fall. Whether or not Reggie took things too far is not for an outsider to decide. The reality is that he took his faith seriously, the Bible seriously, and acted on his convictions. What is most commendable about Reggie, perhaps, is that he could’ve spent the rest of his life fitting into the perfectly packaged box where Christian culture wanted him to remain. He certainly would’ve been more marketable had he stayed. He probably would’ve made more money. But instead, he asked questions, even if it meant being called a heretic by one of his spiritual mentors. He went deeper into the incomprehensible, and therefore pulled his family deeper as well.

“He went through those five years feeling different, but eventually I think he would’ve gotten more comfortable with the things he believed and the things he learned,” Jecolia says. “But he was so passionate about what he was learning that it seemed that it was a little rigid. But I don’t think it always would have been. I think it would have settled down and he wouldn’t have always felt so different, and people would eventually realize, okay, this is just something he learned, and maybe he is on to something. We weren’t trying to start a new religion; he wasn’t trying to be Jewish; he was reading history; taking the time to dive into things that a lot of people don’t.”

Today the Whites have, what some evangelicals might consider, some interesting views about the idea of church. One might conclude they are scarred by how the church handled Reggie. Or maybe they just miss their leader. Reggie was not only the “Minister of Defense”; he was also the minister his family followed and trusted.

What is certain, however, is that, just as Reggie’s death did not stop them from living, nor did it stop them from exploring, from challenging the status quo, from growing and delving deeper into the unfathomable depths of spirituality and how that fits into our everyday lives.

“If I could tell you what my dad really wanted, one of the things was for everyone that he cared about to be close to him,” Jecolia says. “And I think I have a lot of that. And I think that, as a society, if I told someone my dream was to live close to my family and people that I love and see them regularly…well, I wouldn’t say that to a lot of people, because they’d look at me like, ‘Really?’ Because it doesn’t sound like much. But as people, I think we’ve really lost sight of what we are here for. The only way I think that we can really experience God’s love is through our relationships with each other. But it becomes about a lot of other stuff. We’ve lost sight of really simple things that are important.”

There is something special about seeing Sara, Jeremy and Jecolia together. Though they each were forced to handle their grief individually, what stands out most when they are together is their collective joy, all flowing from their love for one another. Though they were each forced to handle their grief in different geographical locations—Charlotte, Elon and Japan, Chapel Hill and Knoxville—now they are all together again as a family. In Mooresville, North Carolina.

“I guess he did pretty good with the time he was here because we all ended up okay,” Jecolia says. “He was the backbone of our family. We really relied on him for a lot, so we didn’t know what to do when he passed, but we got it together. I would hope that we kept it together well enough. I would say the No. 1 thing I would have told him was that, ‘You are remembered the way you wanted to be remembered.’”

And perhaps the greatest testament of this, of Reggie being remembered the way he wanted to be remembered, is not who he became, but who his family has become.

By Stephen Copeland

Stephen Copeland is a staff writer and columnist at Sports Spectrum magazine. This story was published in Sports Spectrum’s Winter 2016 print magazine. Log in HERE to view the issue. Subscribe HERE to receive eight issues of Sports Spectrum a year.