Last summer Pittsburgh Steelers linebacker James Harrison sparked a nation-wide debate and discussion when he posted this caption on Instagram with a picture of his children’s participation trophies:

I came home to find out that my boys received two trophies for nothing, participation trophies! While I am very proud of my boys for everything they do and will encourage them till the day I die, these trophies will be given back until they EARN a real trophy. I’m sorry I’m not sorry for believing that everything in life should be earned and I’m not about to raise two boys to be men by making them believe that they are entitled to something just because they tried their best…cause sometimes your best is not enough, and that should drive you to want to do better…not cry and whine until somebody gives you something to shut u up and keep you happy. #harrisonfamilyvalues

With end-of-the-year banquets for spring sports about to take place and summer sports on the horizon, I thought it would be timely to re-open the conversation. It is an important conversation to have in our ever-changing culture, especially for parents raising children in this society.

On one side of the argument is the idea that participation trophies can inspire a child by giving them something materialistic that represents a positive experience. On the other side is the idea that these unearned rewards set them up for a very negative experience down the road when things don’t go their way.

For those of us who played sports growing up, I think that one of the factors is that we attach trophies to the idea of competition. If everyone gets a trophy, it seems to downplay the value of competition. Some might even go so far as to lump the idea of participation trophies in with socialism.

In our household, we taught our children that they had to earn things when it came to sports or anything that was performance-based. (We also wanted them to know that our unconditional love for them was unearned and had nothing to do with their performance.) Lorri and I believed that our children were not entitled to receive an award in performance-based activities just because they tried hard. We believed that our children needed to learn to work hard, even if they fell short. Failing is a part of life. But these difficult, broken moments were opportunities to teach character and build toughness in preparation for life’s harsh realities.

For example, Tyler was not as good of a basketball player as Luke whenever they were in grade school and middle school. Luke hit his growth spurt in sixth grade. Tyler didn’t hit his until his freshman year in high school. During Tyler’s freshman year of high school, after playing in Luke’s shadow all those years, he thought about quitting. Tyler was playing on the freshman team, while Luke was a candidate for Indiana Mr. Basketball and a McDonald’s All-American.

Throughout these formative years, we did not coddle Tyler; nor did his coaches. We did not pressure him to keep playing. We allowed him to go through the process of disappointment—of not being good enough. I believe Tyler learned some valuable lessons throughout the process, one being that he could be good at other things than basketball like academics. When Tyler severely broke his wrist at the University of North Carolina his freshman year, a reporter bluntly asked him, “What if this is a career-ending injury?” Tyler responded, “Then I’ll just be successful in something other than basketball.”

Many people think that participation trophies increase motivation. I would have to believe that they, in fact, lower motivation. Why would a kid work harder in Little League if he were going to receive the same benefits of a star player on the team? I’ve heard it said that the strongest piece of wood comes from a tree that grew under the tough winds, the hard rains, and the gentle sunshine. It’s the same idea in the human experience.

In adulthood, when a job becomes available, 10 people might apply for a job, but nine will go home without a job. If we give our children an award for just showing up, they won’t know how to handle situations like this in adulthood. Yes, a child’s emotions must be handled delicately and graciously when he or she fails in, say, Little League (I also believe that parents must be intentional in helping their children understand that their worth is not in their child’s performance), but children can also learn some lifelong lessons in these failures that will prepare them for the world they are stepping into and help them mature.

Just recently, Jordan Spieth, the No. 1 golfer in the world, had a meltdown in the final round of the Masters at Augusta National. I cannot imagine how difficult this had to have been for him. However, he will be remembered for his high character and the way he handled the adversity. Not only did he lose, but because he had won the Masters last year, he had to put the green jacket on the winner. But he did it very graciously. I share this story as an example of how trials in athletics have the potential to build character and integrity in our children.

I grew up on a 48-acre farm in Springville, Iowa, the youngest of 12 children. Some of us excelled in sports; some of us had to deal with failure in sports. Some of us excelled in school; some of us had to work extra hard just to get by in school. Whatever the case, my dad always emphasized to us children that we had a responsibility to uphold “the Zeller name” as we grew older. This has nothing to do with excelling in anything; rather, it had to do with displaying character in whatever it was that we did in life and treating people with love and respect wherever we were in life.

I hope that we can raise our children to define success in ways that go far beyond any trophy, award, or performance. Competition—winning and losing, failing and working harder—is a part of life, but it does not have to define who our children are and who they become.

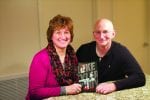

By Steve Zeller

Steve Zeller serves as Vice President of Basketball at DistinXion. He and his wife, Lorri, recently authored a book titled Raising Boys The Zeller Way. The book is available in the Sports Spectrum store. This column was published in Sports Spectrum’s Spring 2016 print magazine. Log in HERE to view the issue. Subscribe HERE to receive eight issues of Sports Spectrum a year.

Steve Zeller serves as Vice President of Basketball at DistinXion. He and his wife, Lorri, recently authored a book titled Raising Boys The Zeller Way. The book is available in the Sports Spectrum store. This column was published in Sports Spectrum’s Spring 2016 print magazine. Log in HERE to view the issue. Subscribe HERE to receive eight issues of Sports Spectrum a year.