On Oct. 4, 1890, Philadelphia outfielder William Ashley “Billy” Sunday (1862-1935) played his final Major League Baseball game. Traded from the woeful Pittsburgh Alleghenys, who finished 23-113, to the National League Phillies for a late-season pennant run, he batted .261—but stole 28 bases in 31 games (with 84 overall).

On Oct. 4, 1890, Philadelphia outfielder William Ashley “Billy” Sunday (1862-1935) played his final Major League Baseball game. Traded from the woeful Pittsburgh Alleghenys, who finished 23-113, to the National League Phillies for a late-season pennant run, he batted .261—but stole 28 bases in 31 games (with 84 overall).

Impressed by his play and popularity, the Phillies offered Sunday a three-year contract at nearly $400 month for the seven-month season. Industrial workers averaged perhaps $380 annually. Billy and his wife, Helen (Nell), had a new baby and were supporting his invalid brother. Having loved the game for years, he signed.

But during the winter of 1890-91, he also agonized. After becoming a Christian in 1886, Sunday became a YMCA teacher-evangelist, and sensed God’s call to full-time ministry. As “Ma” Sunday recalled in 1957, Billy valued his highest salary ever, but “three years looks like a very long time to me now… if you don’t mind, I would like to send a request for my release.” A practical and spiritual woman, she replied, “The Lord isn’t talking to me about it, but if He’s talking to you, pay attention to Him.”

Sunday did. When his Phillies release request was denied, in prayer he sought a sign. Billy would honor his contract with a March 25 departure to join the 1891 ballclub—unless release before then signaled “retirement” into Christian work. Philadelphia’s management, sensing both his uneasiness and the influx of ballplayers from the failed Players League, on March 17 granted his release. Hearing this, Cincinnati offered $500 a month —but Mrs. Sunday settled it: “There is nothing to consider; you promised God to quit.” The YMCA paid $83.33 per month—but in years to come his preaching ministry would touch far greater crowds.

The same Saturday afternoon as Sunday’s finale, James Laurie “Deacon” White (1847-1939) closed his career with the Buffalo Bisons (which he partly owned) in the Players League. Drained business-wise as the players’ revolt against management control, or the reserve clause as it came to be known, fell short, and health-wise by playing 122 games at age 42, he was ready. Younger brother Will—the first major leaguer to wear glasses on the field—welcomed him into the optical business. In later years, he would run a livery stable and garage, and joining (with wife Alice) extended family in Illinois, did maintenance at Aurora College. He was inducted into Baseball’s Hall of Fame in 2013.

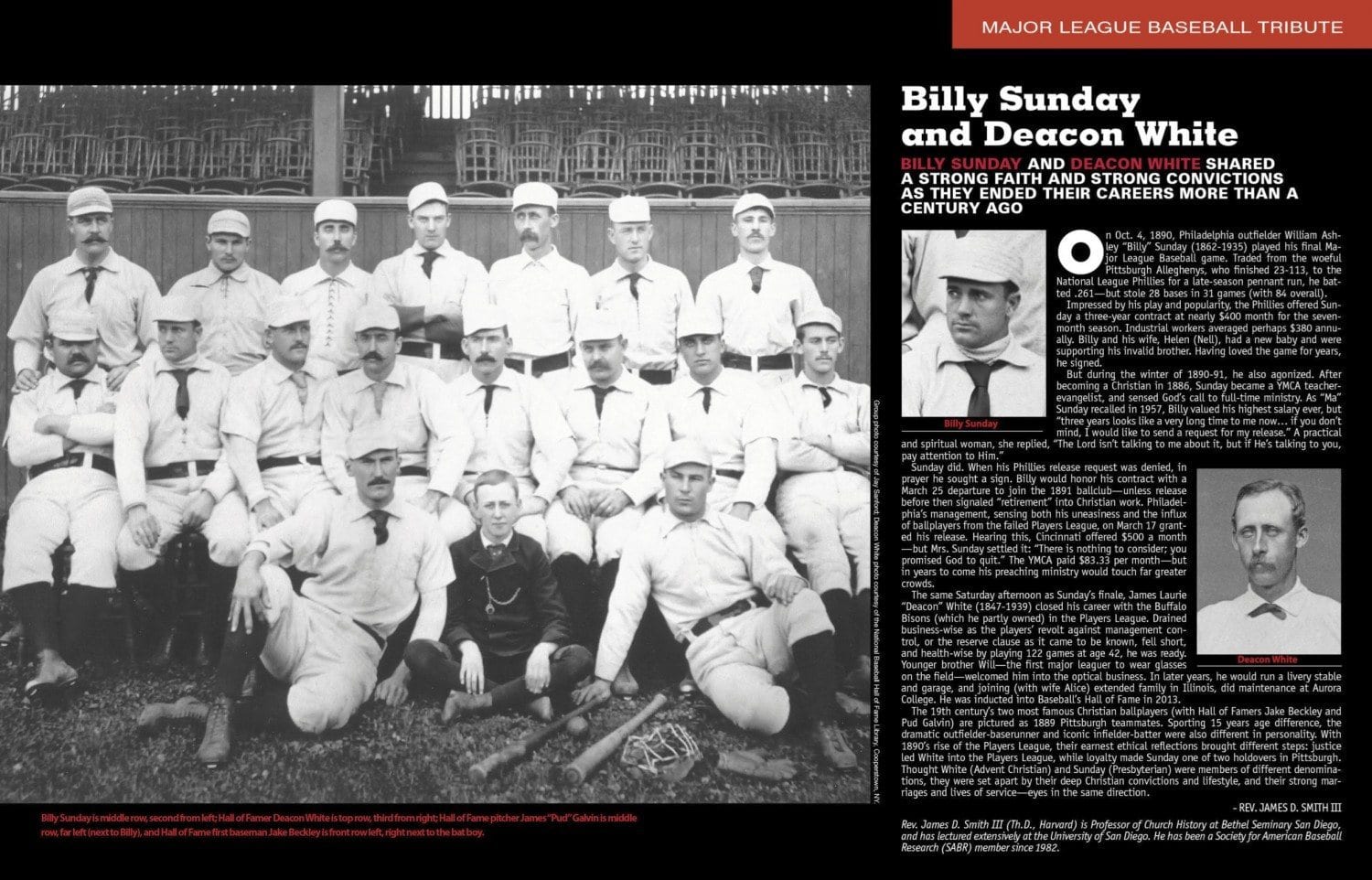

The 19th century’s two most famous Christian ballplayers (with Hall of Famers Jake Beckley and Pud Galvin) are pictured as 1889 Pittsburgh teammates. Sporting 15 years age difference, the dramatic outfielder-baserunner and iconic infielder-batter were also different in personality. With 1890’s rise of the Players League, their earnest ethical reflections brought different steps: justice led White into the Players League, while loyalty made Sunday one of two holdovers in Pittsburgh. Thought White (Advent Christian) and Sunday (Presbyterian) were members of different denominations, they were set apart by their deep Christian convictions and lifestyle, and their strong marriages and lives of service—eyes in the same direction.

By Rev. James D. Smith III

Rev. James D. Smith III (Th.D., Harvard) is Professor of Church History at Bethel Seminary San Diego, and has lectured extensively at the University of San Diego. He has been a Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) member since 1982.