Taylor Morton was a 14-year-old boy, innocent and impressionable, athletic and adventurous, a typical eighth grader whose biggest concern was sports…then maybe school…then maybe girls, whatever “girls” were.

It was an Alabama April. Soon, school would be over. Soon, it would be summer.

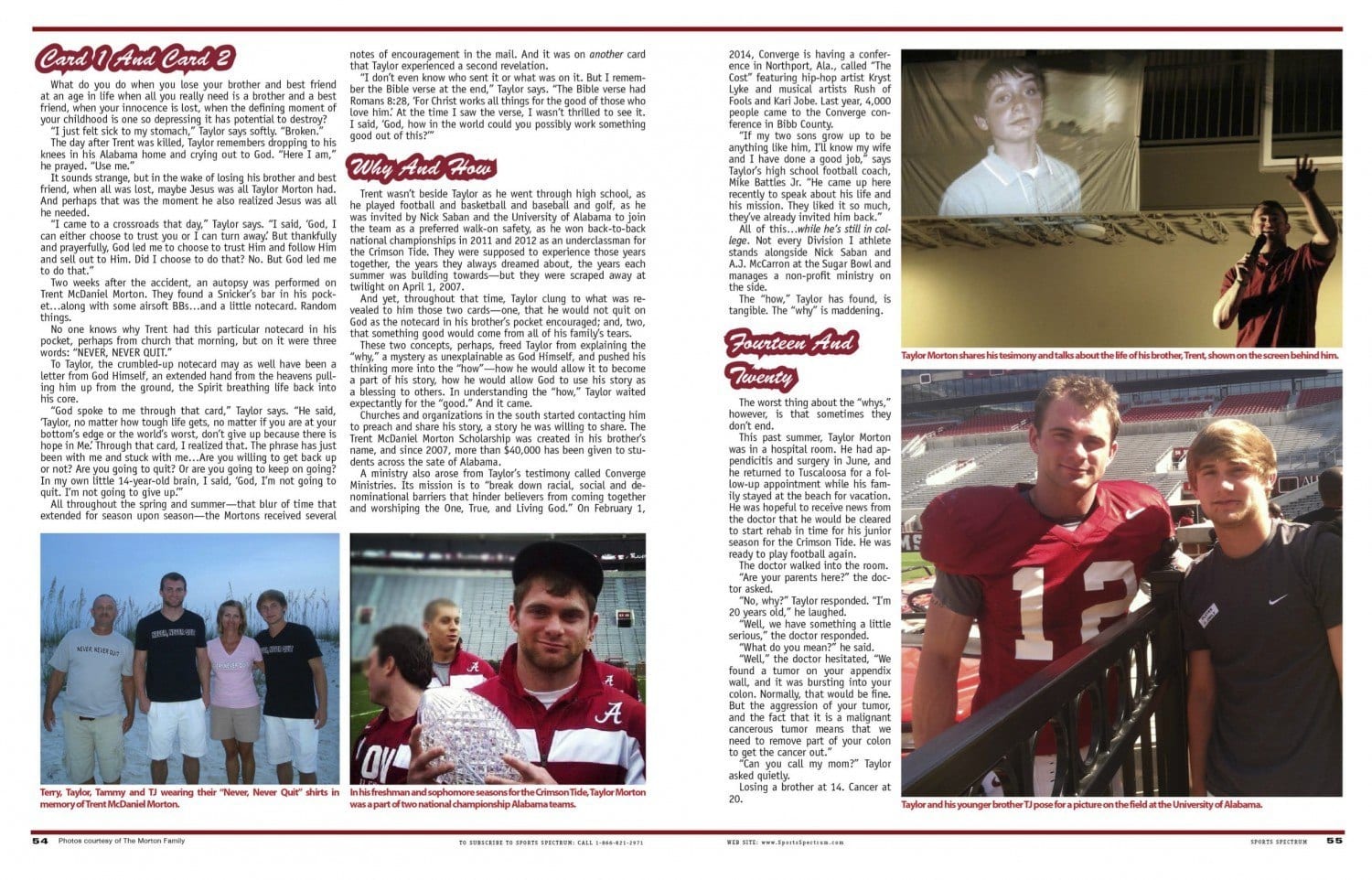

These were the summers of their youth that Taylor and his two younger brothers, Trent (12) and TJ (8) loved to conquer, there in the tiny town of Centreville Ala., there on the banks of the Cahaba River.

Sometimes, they would spend all day at their family’s farm, fishing and four-wheeling and playing imaginary games in those beckoning open fields—there in Neverland, there with one another.

Sometimes, their parents, Terry and Tammy, would take them on a family vacation to the Alabama gulf, and as the three boys kicked in the sand and played in the waves, it’s not far-fetched to think their parents watched from a distance, smiling at the sight of their three beautiful and healthy children playing together, children whom they believed were gifts from the Lord above.

More than anything, summers were spent playing sports. Football. Baseball. Basketball. You name it. Taylor was the best at football; Trent was the best at basketball; and TJ was showing a particular interest in baseball. Sports were at the core of who the Mortons were. With three boys, what can you expect?

Terry coached Taylor in every sport throughout junior high, and coaches at the nearby Bibb County High School looked forward to the day where Taylor and Trent, who were only one grade apart, would complete junior high and play alongside one another in high school. Taylor and Trent looked forward to that day, too. Two brothers. Two best friends. Playing on the same team.

Faith, perhaps, was the only thing more engrained in the Mortons than sports. Every Sunday was spent at Centreville Baptist Church, where Terry was a deacon. Everyone knew the Mortons were about two things, faith and family. They were staples in the Centreville community.

On this particular Sunday, this Sunday on the first of April, with spring making the turn, school nearing the final stretch, and a southern summer on the horizon, Taylor got home from church in the afternoon. Trent had gone fishing with a friend, TJ had gone to a birthday party, and his father had a deacon’s meeting that evening. Taylor stayed home all day.

Nightfall fell upon central Alabama, and Taylor walked outside to take the trash out. A car pulled into the driveway. It was the family of Trent’s friend.

“Where’s your dad at?” they asked, rolling down the window.

“He’s still at a deacon’s meeting,” Taylor responded.

“Okay,” they said, pulling back out of the driveway.

Not much time passed before another car pulled into the Mortons’ driveway. It was the deacons from church. They carried Taylor’s father inside and sat him down, as if he was too weak to walk on his own.

Taylor noticed his father was crying. He had never seen him cry before. Taylor looked up at his father, his eyes posing a question mixed with curiosity and fear.

“Trent has been killed,” his father choked, answering his eyes.

An SUV had slammed into him as he crossed the road on his four-wheeler that evening. He died instantly.

April 1, 2007.

The year that summer never came.

Card 1 And Card 2

What do you do when you lose your brother and best friend at an age in life when all you really need is a brother and a best friend, when your innocence is lost, when the defining moment of your childhood is one so depressing it has potential to destroy?

“I just felt sick to my stomach,” Taylor says softly. “Broken.”

The day after Trent was killed, Taylor remembers dropping to his knees in his Alabama home and crying out to God. “Here I am,” he prayed. “Use me.”

It sounds strange, but in the wake of losing his brother and best friend, when all was lost, maybe Jesus was all Taylor Morton had. And perhaps that was the moment he also realized Jesus was all he needed.

“I came to a crossroads that day,” Taylor says. “I said, ‘God, I can either choose to trust you or I can turn away.’ But thankfully and prayerfully, God led me to choose to trust Him and follow Him and sell out to Him. Did I choose to do that? No. But God led me to do that.”

Two weeks after the accident, an autopsy was performed on Trent McDaniel Morton. They found a Snicker’s bar in his pocket…along with some airsoft BBs…and a little notecard. Random things.

No one knows why Trent had this particular notecard in his pocket, perhaps from church that morning, but on it were three words: “NEVER, NEVER QUIT.”

To Taylor, the crumbled-up notecard may as well have been a letter from God Himself, an extended hand from the heavens pulling him up from the ground, the Spirit breathing life back into his core.

“God spoke to me through that card,” Taylor says. “He said, ‘Taylor, no matter how tough life gets, no matter if you are at your bottom’s edge or the world’s worst, don’t give up because there is hope in Me.’ Through that card, I realized that. The phrase has just been with me and stuck with me…Are you willing to get back up or not? Are you going to quit? Or are you going to keep on going? In my own little 14-year-old brain, I said, ‘God, I’m not going to quit. I’m not going to give up.’”

All throughout the spring and summer—that blur of time that extended for season upon season—the Mortons received several notes of encouragement in the mail. And it was on another card that Taylor experienced a second revelation.

“I don’t even know who sent it or what was on it. But I remember the Bible verse at the end,” Taylor says. “The Bible verse had Romans 8:28, ‘For Christ works all things for the good of those who love him.’ At the time I saw the verse, I wasn’t thrilled to see it. I said, ‘God, how in the world could you possibly work something good out of this?’”

Why And How

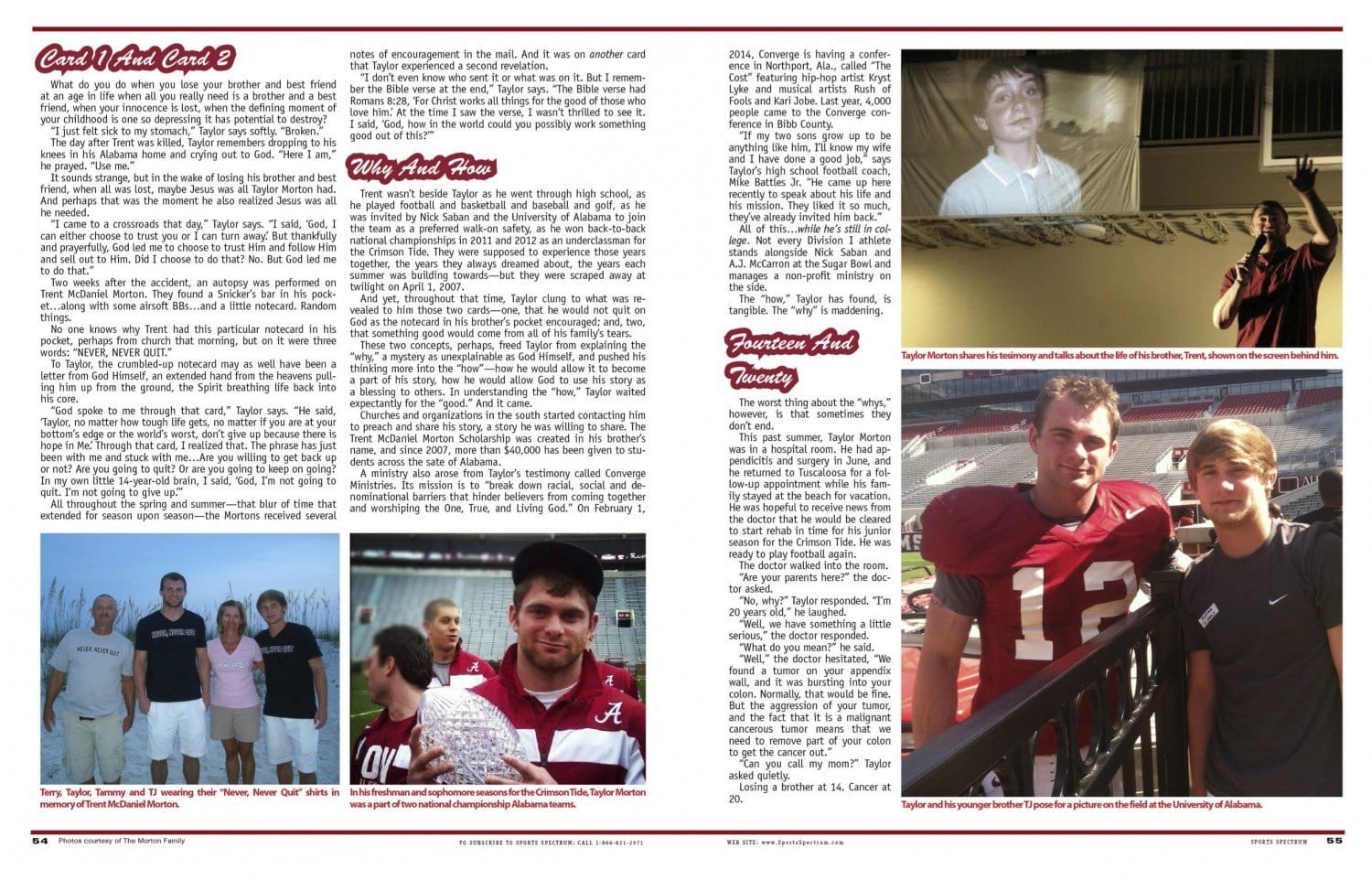

Trent wasn’t beside Taylor as he went through high school, as he played football and basketball and baseball and golf, as he was invited by Nick Saban and the University of Alabama to join the team as a preferred walk-on safety, as he won back-to-back national championships in 2011 and 2012 as an underclassman for the Crimson Tide. They were supposed to experience those years together, the years they always dreamed about, the years each summer was building towards—but they were scraped away at twilight on April 1, 2007.

And yet, throughout that time, Taylor clung to what was revealed to him those two cards—one, that he would not quit on God as the notecard in his brother’s pocket encouraged; and, two, that something good would come from all of his family’s tears.

These two concepts, perhaps, freed Taylor from explaining the “why,” a mystery as unexplainable as God Himself, and pushed his thinking more into the “how”—how he would allow it to become a part of his story, how he would allow God to use his story as a blessing to others. In understanding the “how,” Taylor waited expectantly for the “good.” And it came.

Churches and organizations in the south started contacting him to preach and share his story, a story he was willing to share. The Trent McDaniel Morton Scholarship was created in his brother’s name, and since 2007, more than $40,000 has been given to students across the sate of Alabama.

A ministry also arose from Taylor’s testimony called Converge Ministries. Its mission is to “break down racial, social and denominational barriers that hinder believers from coming together and worshiping the One, True, and Living God.” On February 1, 2014, Converge is having a conference in Northport, Ala., called “The Cost” featuring hip-hop artist Kryst Lyke and musical artists Rush of Fools and Kari Jobe. Last year, 4,000 people came to the Converge conference in Bibb County.

“If my two sons grow up to be anything like him, I’ll know my wife and I have done a good job,” says Taylor’s high school football coach, Mike Battles Jr. “He came up here recently to speak about his life and his mission. They liked it so much, they’ve already invited him back.”

All of this…while he’s still in college. Not every Division I athlete stands alongside Nick Saban and A.J. McCarron at the Sugar Bowl and manages a non-profit ministry on the side.

The “how,” Taylor has found, is tangible. The “why” is maddening.

Fourteen And Twenty

The worst thing about the “whys,” however, is that sometimes they don’t end.

This past summer, Taylor Morton was in a hospital room. He had appendicitis and surgery in June, and he returned to Tuscaloosa for a follow-up appointment while his family stayed at the beach for vacation. He was hopeful to receive news from the doctor that he would be cleared to start rehab in time for his junior season for the Crimson Tide. He was ready to play football again.

The doctor walked into the room.

“Are your parents here?” the doctor asked.

“No, why?” Taylor responded. “I’m 20 years old,” he laughed.

“Well, we have something a little serious,” the doctor responded.

“What do you mean?” he said.

“Well,” the doctor hesitated, “We found a tumor on your appendix wall, and it was bursting into your colon. Normally, that would be fine. But the aggression of your tumor, and the fact that it is a malignant cancerous tumor means that we need to remove part of your colon to get the cancer out.”

“Can you call my mom?” Taylor asked quietly.

Losing a brother at 14. Cancer at 20.

Living and Gaining

Taylor went back to his apartment. His girlfriend came over. His family cut vacation short and headed back to Tuscaloosa. How much more can a family handle?

“I was just sitting there, thinking, and my mind started wandering, ‘Is this it? What’s going to happen?’” Taylor reflects. “But then something dawned on me: I can take this on. ‘You know what?’ I told God, ‘If I have to go through chemo or treatments, I’m ready to start it and I’m ready to fight this fight. God, if it’s Your will to take me tomorrow or the next year, or now, whatever, Your will be done.’ I was scared. I was nervous. I was 20 years old and found out I had cancer….But did I take it on myself? No. God was right there with me.”

Perhaps when you realize dying is gaining, it really allows you to live.

It frees you.

“No matter what happens in life, I go back to that verse,” Taylor says. “God will make something good happen. The Bible says, ‘to live is Christ, to die is gain.’ I mean, think about that, to die is gain. When I die, I will spend eternity in heaven. Nothing is greater than that. But while I’m living here, I’m living for Christ, and there’s nothing better than that! It’s a win-win situation. That reflects on what Romans 8:28 says. All things. The good. The bad. And the ugly. He works all things together for His glory.”

The doctors went in and removed the right part of Taylor’s colon. They took it head on. No treatment. No shots. No radiation. And as of right now, Taylor Morton is cancer free. In the spring, he’ll have a chance to play football again for the University of Alabama.

“Taylor is one of the few I’ve been around, that what you see is what you get,” Battles continues. “He could take on something as traumatic as losing a younger brother and having to deal with cancer, and I don’t know too many people who could handle that, but he was able to take those two unfortunate incidents and turn it around to change people’s lives.”

And so, Taylor Morton will live ‘til he gains, never quit and notice the good.

“I have seen God make something beautiful out of something so ugly,” Taylor says. “I’ve seen Him write a story, write a book. And I’ve seen it firsthand. I’m just the pages He is writing on. I don’t necessarily know why all this has happened, but I’m thankful God has chosen to use these things I’ve been through to help other people. I’m blessed to have that. ‘Blessed to have my brother taken?’ you might ask. ‘Blessed to have cancer?’ Oh, it hurts. Nothing will ever change that. But the more I grow in Christ, the more I fall in love with Christ, the more I see how blessed I am to have gone through that, to be able to share the love of Jesus Christ with others because of it. It’s a beautiful thing.”

By Stephen Copeland

Stephen Copeland is a staff writer and columnist at Sports Spectrum.