Dave Dravecky had overcome cancer surgery on his throwing arm and come back to pitch again in the major leagues. Not since watching helplessly as Lou Gehrig battled amyotrophic lateral sclerosis had the nation so intimately identified with a ballplayer’s struggle with illness. Yet on Aug. 10, 1989, a capacity crowd witnessed heartwarming history as Dravecky started for the Giants against the Cincinnati Reds. He had not pitched in Candlestick since May 2, 1988, and the scoreboard flashed a giant “Welcome back, Dave!” Some who had come from out of town simply to see a professional baseball game in venerable Candlestick Park were treated to a very special celebration indeed.

Less than one year earlier, on Oct. 7, 1988 – ironically Dave and Janice Dravecky’s 10th wedding anniversary – doctors had removed the tumor and nearly half of the deltoid muscle of Dave’s pitching arm. It had been a season of pain and frustration of Dave, in a year that held great promise.

“When I started for the Giants on opening day, and we beat the Dodgers 5-1, I though, ‘This is going to be Dave Dravecky’s year,’” he recalled. “God certainly had a different plan for us in 1988.”

He started four more games for the Giants that year, complaining of stiffness in his left shoulder after each outing. Following arthroscopic surgery in June, he made one last start in a minor league rehabilitation game. Allowing 11 runs in less than three innings, he left the game – and the season.

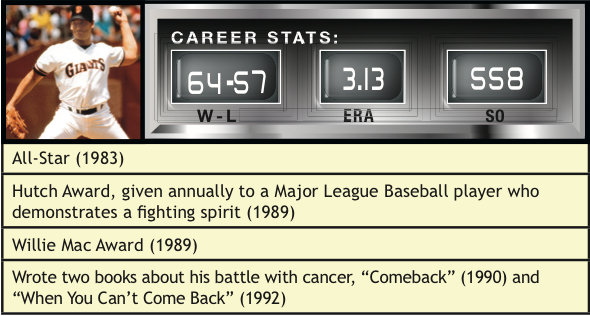

The cancer was diagnosed in late September and the operation performed a week later. The All-Star hurler instrumental in the Giants’ 1987 drive toward the National League West Championship was down and out for 1988.

The tumor was gone but it was uncertain whether Dravecky’s future in baseball was as well. He remained optimistic, however, confidently expecting to report to spring training after his winter-long rehabilitation. And throughout their ordeal with the disease and recovery, Dave and his wife Janice exhibited an unnatural sense of calm and acceptance in spite of the uncertainty of their situation.

“I wouldn’t be truthful if I said I didn’t have any concern at all,” he said then. “But I can honestly say that during that period, for the first time in my life, I experienced peace that surpasses understanding. This was a tremendous relief for our family.”

At home in Ohio, his therapy progressed remarkably well. Late in March he was amazingly allowed to report to training camp. And then came the opportunity to test the arm in game situations. The first was a historic event on July 23 at Herbert Field in Stockton, Calif. Before a standing-room-only crowed of well-wishers and media, Dravecky threw a complete-game five-hit shutout for the San Jose Giants (Class-A). Pleased with his progress after two additional complete-game victories, the Giants and his doctors determined that Dravecky was ready to return to the majors.

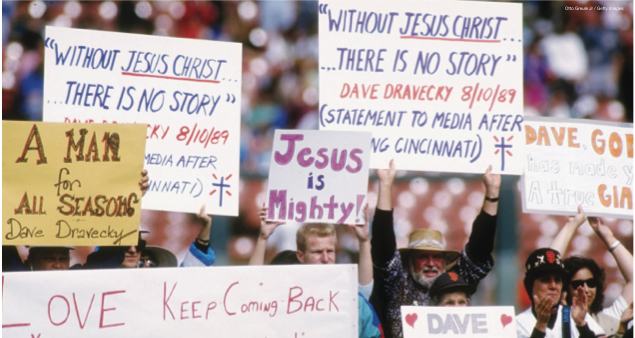

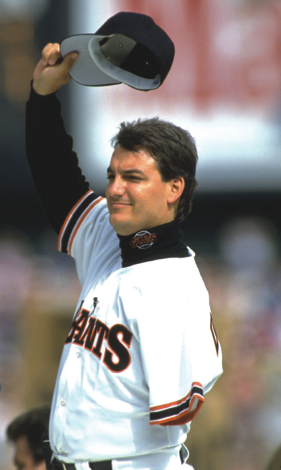

The miracle had happened. Dravecky had come back. On Aug. 10, 1989, amid repeated, thunderous standing ovations, Dravecky not only returned to pitch before the home crowed, he also earned a win for his team against the beleaguered Reds. He was back, and it wasn’t a token appearance.

“I though, ‘Okay, here we go, back in baseball. Everything’s going to be fine.’ I was back in the groove. I was one of the guys again,” said Dravecky. “I could start getting in gear for what lay ahead for the rest of the season, and I could start looking ahead to the playoffs.”

Then suddenly Cinderella’s other glass slipper smashed in pieces on the infield grass. In his second start, at Montreal, the humerus bone in his pitching arm snapped as he delivered a pitch. His comeback season was over almost as soon as it had begun, and now he lay writhing in pain on the ground. His arm was broken, but surprising to some, his faith was intact.

“What is so unique about this is, why didn’t my arm break before Aug. 10, when I came back? As I went along, I built up strength. Why didn’t it break in those three rehab games? And why was I allowed to come back and pitch as well as I did, and then to break my arm five days later?

“Those are questions where I see the hand of God. So for me it wasn’t ‘Why God?’ but ‘What is going to happen next? There is something big going on here, and I’d like to know what it is.’”

The doctors had warned that a break was a possibility. As part of the procedure to remove the tumor, the bone had been temporarily frozen and would be brittle for some time. Still there was hope for Dravecky’s career. The break, when healed, would make the bone stronger than before. He faced his newest challenges with familiar confidence.

“I expressed the hope that I would come back again to play if it was at all possible. After breaking the arm that first time, all indications from the doctors were very optimistic of my being able to come back. The arm was going to be stronger and there was no reason for me to think otherwise. Retirement was the furthest thing from my mind.”

Although unable to play, he remained an active part of the Giants’ stretch run.

“It was important to me to be in the dugout with my team during the pennant drive because I wanted to lend support to them. They had been with me through thick and thin, through the whole year of 1988 and 1989.”

So in spite of the drain on his recovering body, Dravecky stayed with his team through the pressure-packed end of the season.

It was during the jubilant celebration at the mound after the Giants had captured the National League championship that Dravecky was inadvertently bumped by another player. He knew at once that the brittle arm had been broken again.

“It was a freak accident, but when I look back, I realize that it was all part of the process of coming to a decision to retire,” he said then. “And really all that means is that I want to be available to what God has in store for me from this point on. Baseball is over. I was given my day in the sun – it was for a season. Now I have this window of opportunity to share what has happened in my life. And it will be for a season. However long that is, I want to be prepared for it.”

“When I look back, I have no regrets about my career of seven years in the major leagues,” Dave Dravecky said. “I’ve had the opportunity to be part of an All-Star game, where I felt out of place among some legitimate all-stars as far as I was concerned. And what an honor it was to be in two World Series and three playoff series.”

But if a reporter asked what was the most memorable moment of Dravecky’s career he could be sure of the answer.

“It was in 1981, when I was in the San Diego Padres’ farm system. A teammate led me to open the Bible and see what it meant to me in a personal way.”

This teammate challenged Dravecky that he needed to have a personal relationship with God by believing in His Son, Jesus Christ.

It is that relationship which Dravecky credits for the ability to come out on top of the challenges he has faced.

“If it weren’t for Jesus Christ, who knows where I’d be. I’m sure most people think I’m in the pits, but I don’t think I am. I’m as excited as I’ve ever been about the future, even though I don’t know exactly what it is.”

Dravecky never played baseball again. He relied heavily on medical advice to direct and then terminate his playing career, but his trust has remained in the One who gave him hope in the darkest times. And he is confident whatever the future holds, there can be no greater comeback than that.

“We’re going in a new direction. We’re going to start a new life. God has given us a peace about that, and the desire of our heart is to be in His will. I’m actually going to be able to retire, and come out of retirement and then start all over again.”

Dravecky had his arm amputated two years after retiring. It was necessary to save his life.

But why? Dravecky wondered.

For 16 months, he and Jan went through counseling for depression. Finally, joyfully, they emerged as confident encouragers.

Both wrote books in 1996 – Dave’s was called The Worth of a Man, and Jan’s was A Joy I’d Never Known. Both were co-authored by C.W. Neal and both form the core of Dave Dravecky’s Outreach of Hope, which Dave says may be the only ministry around that encourages cancer patients and amputees from a spiritual perspective.

Dave Dravecky also wrote a Christian motivational book, Called Up, released in 2004.

Although Dave is president of Outreach of Hope, he is also a volunteer, helping Jan and others with the work on the most elementary level.

“What I’m coming to understand is I need to be a servant leader,” Dave said then. “That’s the focus of my leadership position at the Outreach of Hope. And I want to incorporate everyone there into the vision of the ministry and give them ownership, so that they are as excited about that vision as we are.”

Because the heart-tugging nature of his life story, he had plenty of opportunities to speak after his surgery to remove his arm.

Dave’s book, Worth Of A Man, is an apparent break from his baseball past. In it, he explored territory that one would expect pastors, professors, and psychologists to examine.

With warm anecdotes that seemed to pulse directly from his heart, Dravecky introduced readers to many of his friends, many who are were plain folks who had suffered. Dravecky bore their burdens in a way that make readers want to as well.

One of the book’s most powerful points was the trappings of American culture; that the seemingly endless career pursuits and recreational distractions fade swiftly into insignificance when cancer enters a life.

“(The) book has been another phase in my life that has caused me to go a little bit deeper with asking that question, ‘Who am I?’” said Dravecky. “That has been significant. You know what’s interesting? The journey starts off complicated as a Christian. But as you go through the valleys of life, all of a sudden God makes you realize it’s not the complicated life, it’s a simplified life.”

By Rick Wattman – Allen Palmeri also contributed to this article

By Rick Wattman – Allen Palmeri also contributed to this article

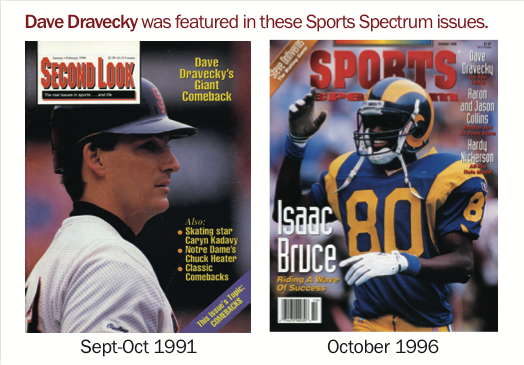

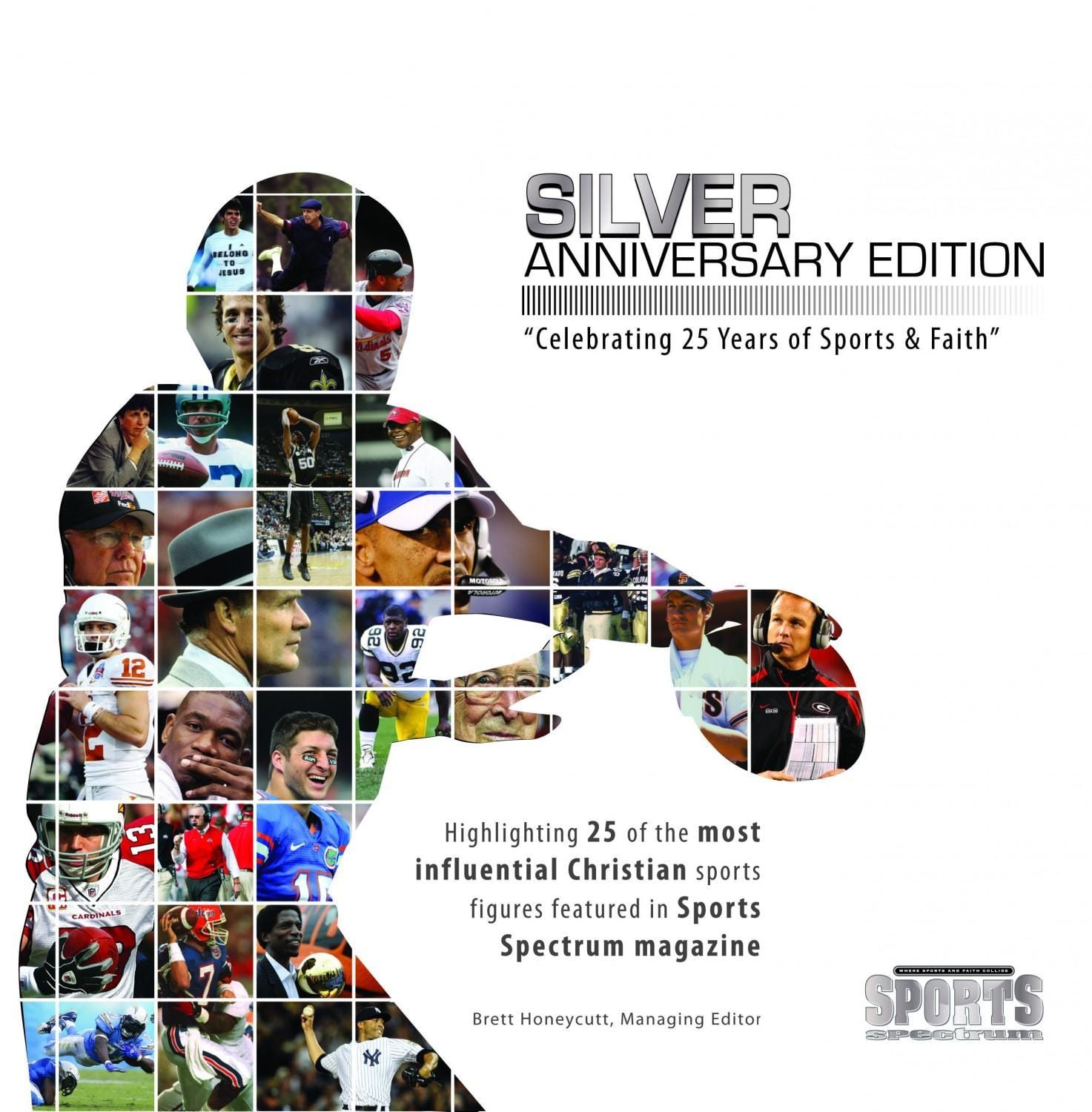

This story comes from the pages of Sports Spectrum’s Silver Anniversary Edition