Eddie Perez was watching a television in a room off the Atlanta bullpen when he heard a knock on the door. The Braves coach knew it was the home run ball he had just seen burst off the bat of a hometown prodigy taking his first swing in the big leagues.

Eddie Perez was watching a television in a room off the Atlanta bullpen when he heard a knock on the door. The Braves coach knew it was the home run ball he had just seen burst off the bat of a hometown prodigy taking his first swing in the big leagues.

“When we were watching in there, we got excited and we hear pop!” says Perez, who sensed more than the usual fan celebration at Turner Field. “Everybody was going crazy. It was like the birth of a new star. There was a new star coming out in Atlanta. It was the kid that everybody was expecting to be the star. That was the beginning of a new era.”

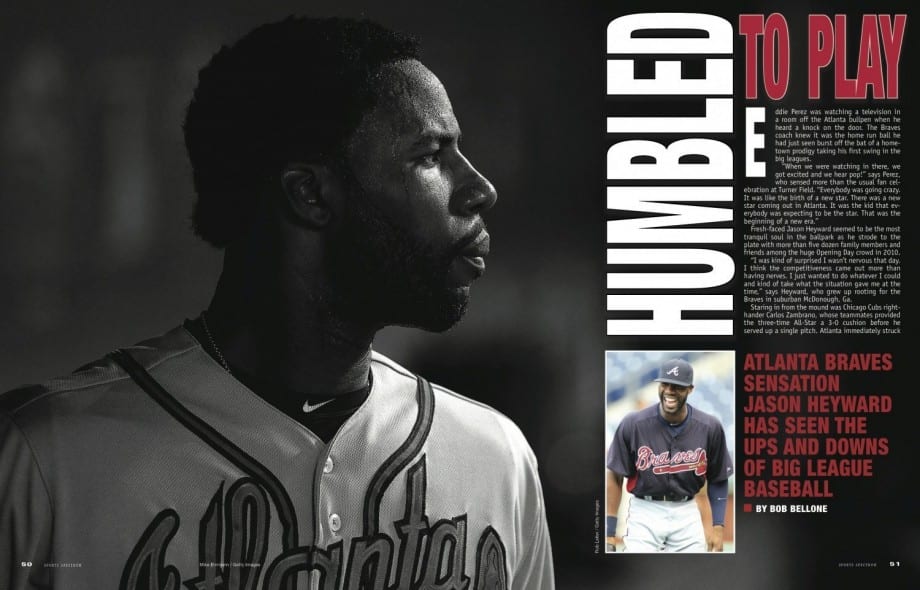

Fresh-faced Jason Heyward seemed to be the most tranquil soul in the ballpark as he strode to the plate with more than five dozen family members and friends among the huge Opening Day crowd in 2010.

“I was kind of surprised I wasn’t nervous that day. I think the competitiveness came out more than having nerves. I just wanted to do whatever I could and kind of take what the situation gave me at the time,” says Heyward, who grew up rooting for the Braves in suburban McDonough, Ga.

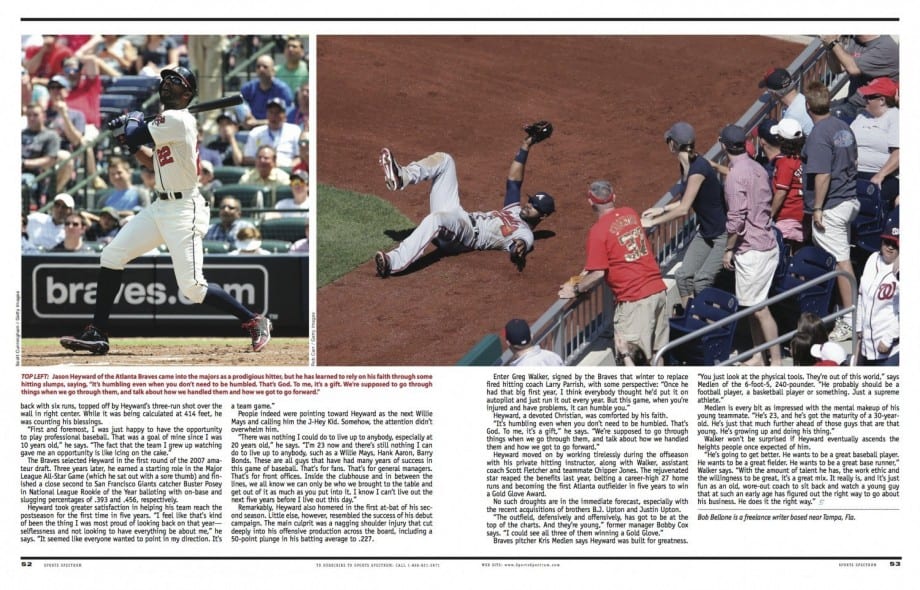

Staring in from the mound was Chicago Cubs right-hander Carlos Zambrano, whose teammates provided the three-time All-Star a 3-0 cushion before he served up a single pitch. Atlanta immediately struck back with six runs, topped off by Heyward’s three-run shot over the wall in right center. While it was being calculated at 414 feet, he was counting his blessings.

“First and foremost, I was just happy to have the opportunity to play professional baseball. That was a goal of mine since I was 10 years old,” he says. “The fact that the team I grew up watching gave me an opportunity is like icing on the cake.”

The Braves selected Heyward in the first round of the 2007 amateur draft. Three years later, he earned a starting role in the Major League All-Star Game (which he sat out with a sore thumb) and finished a close second to San Francisco Giants catcher Buster Posey in National League Rookie of the Year balloting with on-base and slugging percentages of .393 and .456, respectively.

Heyward took greater satisfaction in helping his team reach the postseason for the first time in five years. “I feel like that’s kind of been the thing I was most proud of looking back on that year— selflessness and not looking to have everything be about me,” he says. “It seemed like everyone wanted to point in my direction. It’s a team game.”

People indeed were pointing toward Heyward as the next Willie Mays and calling him the J-Hey Kid. Somehow, the attention didn’t overwhelm him.

“There was nothing I could do to live up to anybody, especially at 20 years old,” he says. “I’m 23 now and there’s still nothing I can do to live up to anybody, such as a Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Barry Bonds. These are all guys that have had many years of success in this game of baseball. That’s for fans. That’s for general managers. That’s for front offices. Inside the clubhouse and in between the lines, we all know we can only be who we brought to the table and get out of it as much as you put into it. I know I can’t live out the next five years before I live out this day.”

Remarkably, Heyward also homered in the first at-bat of his second season. Little else, however, resembled the success of his debut campaign. The main culprit was a nagging shoulder injury that cut deeply into his offensive production across the board, including a 50-point plunge in his batting average to .227.

Enter Greg Walker, signed by the Braves that winter to replace fired hitting coach Larry Parrish, with some perspective: “Once he had that big first year, I think everybody thought he’d put it on autopilot and just run it out every year. But this game, when you’re injured and have problems, it can humble you.”

Heyward, a devoted Christian, was comforted by his faith.

“It’s humbling even when you don’t need to be humbled. That’s God. To me, it’s a gift,” he says. “We’re supposed to go through things when we go through them, and talk about how we handled them and how we got to go forward.”

Heyward moved on by working tirelessly during the offseason with his private hitting instructor, along with Walker, assistant coach Scott Fletcher and teammate Chipper Jones. The rejuvenated star reaped the benefits last year, belting a career-high 27 home runs and becoming the first Atlanta outfielder in five years to win a Gold Glove Award.

No such droughts are in the immediate forecast, especially with the recent acquisitions of brothers B.J. Upton and Justin Upton.

“The outfield, defensively and offensively, has got to be at the top of the charts. And they’re young,” former manager Bobby Cox says. “I could see all three of them winning a Gold Glove.”

Braves pitcher Kris Medlen says Heyward was built for greatness. “You just look at the physical tools. They’re out of this world,” says Medlen of the 6-foot-5, 240-pounder. “He probably should be a football player, a basketball player or something. Just a supreme athlete.”

Medlen is every bit as impressed with the mental makeup of his young teammate. “He’s 23, and he’s got the maturity of a 30-year-old. He’s just that much further ahead of those guys that are that young. He’s growing up and doing his thing.”

Walker won’t be surprised if Heyward eventually ascends the heights people once expected of him.

“He’s going to get better. He wants to be a great baseball player. He wants to be a great fielder. He wants to be a great base runner,” Walker says. “With the amount of talent he has, the work ethic and the willingness to be great, it’s a great mix. It really is, and it’s just fun as an old, wore-out coach to sit back and watch a young guy that at such an early age has figured out the right way to go about his business. He does it the right way.”

By Bob Bellone

Bob Bellone is a freelance writer based near Tampa, Fla.