The “Hello Kitty” poster was the first clue: Something was amiss. This couldn’t actually be the office of an NFL head coach, could it?

Where were the pithy motivational placards about success, endurance and teamwork? Where were the ostentatious odes to football or the coach’s own achievements? And how did this girly paraphernalia make it past security? This is, after all, the NFL, which has annals filled with stories of blustering men who rule football fiefdoms like medieval lords and treat their serfs accordingly.

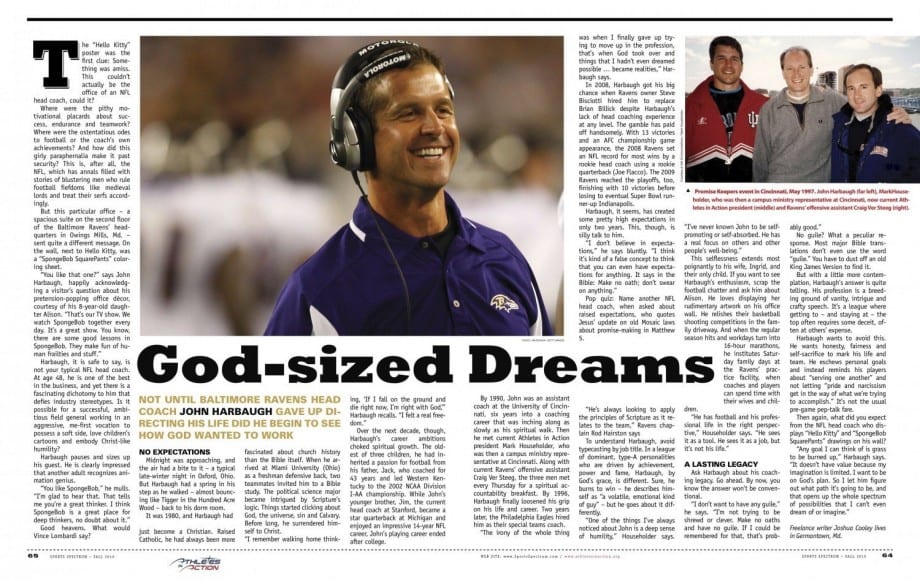

But this particular office – a spacious suite on the second floor of the Baltimore Ravens’ headquarters in Owings Mills, Md. – sent quite a different message. On the wall, next to Hello Kitty, was a “SpongeBob SquarePants” coloring sheet.

“You like that one?” says John Harbaugh, happily acknowledging a visitor’s question about his pretension-popping office décor, courtesy of his 8-year-old daughter Alison. “That’s our TV show. We watch SpongeBob together every day. It’s a great show. You know, there are some good lessons in SpongeBob. They make fun of human frailties and stuff.”

Harbaugh, it is safe to say, is not your typical NFL head coach. At age 48, he is one of the best in the business, and yet there is a fascinating dichotomy to him that defies industry stereotypes. Is it possible for a successful, ambitious field general working in an aggressive, me-first vocation to possess a soft side, love children’s cartoons and embody Christ-like humility?

Harbaugh pauses and sizes up his guest. He is clearly impressed that another adult recognizes animation genius.

“You like SpongeBob,” he mulls. “I’m glad to hear that. That tells me you’re a great thinker. I think SpongeBob is a great place for deep thinkers, no doubt about it.”

Good heavens. What would Vince Lombardi say?

No Expectations

Midnight was approaching, and the air had a bite to it – a typical late-winter night in Oxford, Ohio. But Harbaugh had a spring in his step as he walked – almost bouncing like Tigger in the Hundred Acre Wood – back to his dorm room.

It was 1980, and Harbaugh had just become a Christian. Raised Catholic, he had always been more fascinated about church history than the Bible itself. When he arrived at Miami University (Ohio) as a freshman defensive back, two teammates invited him to a Bible study. The political science major became intrigued by Scripture’s logic. Things started clicking about God, the universe, sin and Calvary. Before long, he surrendered himself to Christ.

“I remember walking home thinking, ‘If I fall on the ground and die right now, I’m right with God,’” Harbaugh recalls. “I felt a real freedom.”

Over the next decade, though, Harbaugh’s career ambitions choked spiritual growth. The oldest of three children, he had inherited a passion for football from his father, Jack, who coached for 43 years and led Western Kentucky to the 2002 NCAA Division I-AA championship. While John’s younger brother, Jim, the current head coach at Stanford, became a star quarterback at Michigan and enjoyed an impressive 14-year NFL career, John’s playing career ended after college.

By 1990, John was an assistant coach at the University of Cincinnati, six years into a coaching career that was inching along as slowly as his spiritual walk. Then he met current Athletes in Action president Mark Householder, who was then a campus ministry representative at Cincinnati. Along with current Ravens’ offensive assistant Craig Ver Steeg, the three men met every Thursday for a spiritual accountability breakfast. By 1996, Harbaugh finally loosened his grip on his life and career. Two years later, the Philadelphia Eagles hired him as their special teams coach.

“The irony of the whole thing was when I finally gave up trying to move up in the profession, that’s when God took over and things that I hadn’t even dreamed possible … became realities,” Harbaugh says.

In 2008, Harbaugh got his big chance when Ravens owner Steve Bisciotti hired him to replace Brian Billick despite Harbaugh’s lack of head coaching experience at any level. The gamble has paid off handsomely. With 13 victories and an AFC championship game appearance, the 2008 Ravens set an NFL record for most wins by a rookie head coach using a rookie quarterback (Joe Flacco). The 2009 Ravens reached the playoffs, too, finishing with 10 victories before losing to eventual Super Bowl runner-up Indianapolis.

Harbaugh, it seems, has created some pretty high expectations in only two years. This, though, is silly talk to him.

“I don’t believe in expectations,” he says bluntly. “I think it’s kind of a false concept to think that you can even have expectations for anything. It says in the Bible: Make no oath; don’t swear on anything.”

Pop quiz: Name another NFL head coach, when asked about raised expectations, who quotes Jesus’ update on old Mosaic laws about promise-making in Matthew 5.

“He’s always looking to apply the principles of Scripture as it relates to the team,” Ravens chaplain Rod Hairston says.

To understand Harbaugh, avoid typecasting by job title. In a league of dominant, type-A personalities who are driven by achievement, power and fame, Harbaugh, by God’s grace, is different. Sure, he burns to win – he describes himself as “a volatile, emotional kind of guy” – but he goes about it differently.

“One of the things I’ve always noticed about John is a deep sense of humility,” Householder says. “I’ve never known John to be self-promoting or self-absorbed. He has a real focus on others and other people’s well-being.”

This selflessness extends most poignantly to his wife, Ingrid, and their only child. If you want to see Harbaugh’s enthusiasm, scrap the football chatter and ask him about Alison. He loves displaying her rudimentary artwork on his office wall. He relishes their basketball shooting competitions in the family driveway. And when the regular season hits and workdays turn into 16-hour marathons, he institutes Saturday family days at the Ravens’ practice facility, when coaches and players can spend time with their wives and children.

“He has football and his professional life in the right perspective,” Householder says. “He sees it as a tool. He sees it as a job, but it’s not his life.”

A Lasting Legacy

Ask Harbaugh about his coaching legacy. Go ahead. By now, you know the answer won’t be conventional.

“I don’t want to have any guile,” he says. “I’m not trying to be shrewd or clever. Make no oaths and have no guile. If I could be remembered for that, that’s probably good.”

No guile? What a peculiar response. Most major Bible translations don’t even use the word “guile.” You have to dust off an old King James Version to find it.

But with a little more contemplation, Harbaugh’s answer is quite telling. His profession is a breeding ground of vanity, intrigue and crafty speech. It’s a league where getting to – and staying at – the top often requires some deceit, often at others’ expense.

Harbaugh wants to avoid this. He wants honesty, fairness and self-sacrifice to mark his life and team. He eschews personal goals and instead reminds his players about “serving one another” and not letting “pride and narcissism get in the way of what we’re trying to accomplish.” It’s not the usual pre-game pep-talk fare.

Then again, what did you expect from the NFL head coach who displays “Hello Kitty” and “SpongeBob SquarePants” drawings on his wall?

“Any goal I can think of is grass to be burned up,” Harbaugh says. “It doesn’t have value because my imagination is limited. I want to be on God’s plan. So I let him figure out what path it’s going to be, and that opens up the whole spectrum of possibilities that I can’t even dream of or imagine.”

Freelance writer Joshua Cooley lives in Germantown, Md.