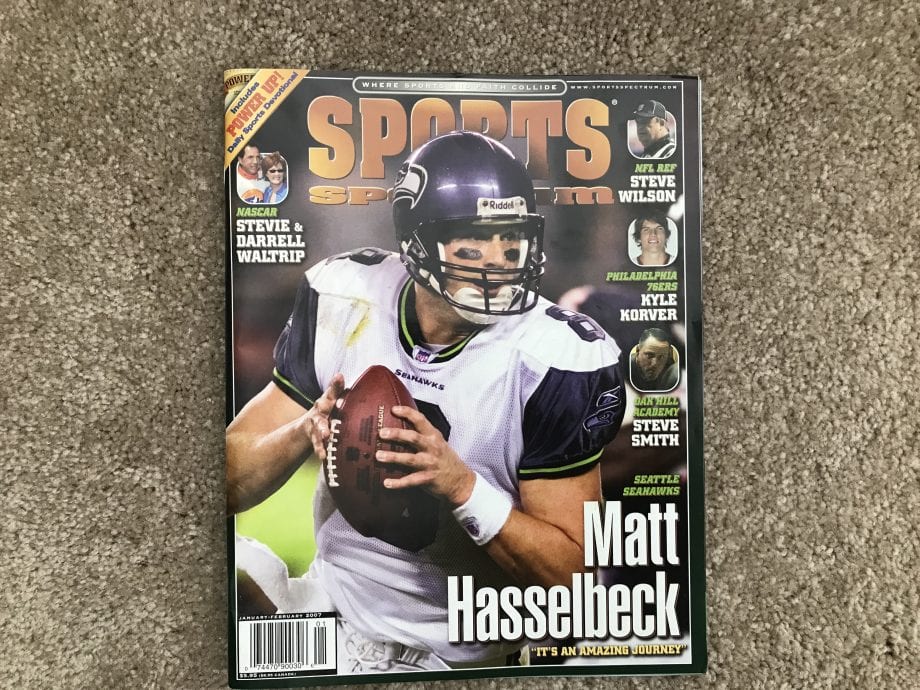

The following article was originally posted in the January-February 2007 edition of Sports Spectrum Magazine.

The Amazing Journey of Matt Hasselbeck

by Gail Wood

It was here, in the poverty-torn country of Jamaica, while sitting next to a man grotesquely disfigured by leprosy, that Matt Hasselbeck began his unexpected journey to the NFL, to the Pro Bowl, and to the Super Bowl.

It was here, as Hasselbeck watched with amazement a man who had lost his fingers, ears, nose, and sight to leprosy joyfully praising God in prayer and in song, that the Seattle Seahawks quarterback discovered the meaning of contentment and commitment.

Ten years ago, Hasselbeck, as a sophomore at Boston College, took a 10-day missionary trip with 16 classmates and Father Ted Dziak to Jamaica. Hasselbeck came back a different man.

“No question it was a life-changing experience,” the Seahawks quarterback says.

The trip to Riverton City, a shanty town built on a garbage dump near Jamaica’s capital city of Kingston, gave Hasselbeck a grim, up-close look at desperate poverty, something the son of an NFL tight end growing up in Boston had never seen. On several days of the trip, Hasselbeck worked in a home for elderly lepers.

He cleaned, scraped, then painted a bathroom in the home. In the evenings after a day’s work, he’d join the lepers for song and worship. It was then that Hasselbeck met George McVee, the man disfigured by leprosy.

The first evening, Hasselbeck was the last to arrive and only one chair remained. It was next to McVee.

“I’m ashamed to say this, but it was hard to look at him,” Hasselbeck says. “I didn’t really want to sit next to him. His leprosy was so much worse than everyone else’s. They said it wasn’t contagious, but I was a kid. I didn’t know.”

With Hasselbeck seated, McVee held a harmonica between his stumps and played hymns. And everyone sang. There was no other music other than the voices and McVee’s harmonica.

In between songs, McVee spoke, reciting long passages of Scripture and poems he had composed. One of his poems he called, “My Cup Runneth Over.”

“They he’d say, ‘Thank you, Jesus. Thank you, Jesus.'” Hasselbeck recalls.

And Hasselbeck looked at this deformed man and the others in wonder.

“I’m saying to myself these people should be angry. What they were born into — poverty, poor health. What do they have to be happy about?” Hasselbeck says. “But in their eyes, it was the exact opposite. Their attitude was what my attitude should have been like.”

After leaving the home for lepers, Hasselbeck spent several days at a Catholic-supported school for children ages 3 to 6. The children wore uniforms given to them by the school. Many of them had no shoes. None of them had eaten before coming to school.

They all lived in homes with tin roofs, no windows, no electricity, and no running water. While there, Hasselbeck lived in one of those shanty homes, sharing it with a mother, her 22-year-old and 10-year-old sons, and her grandmother.

One afternoon Hasselbeck was outside this one-room school playing games with the children. Suddenly, a grief-stricken woman clutching her dead son ran toward the school, screaming for help. Her 4-year-old son had fallen into a latrine and drowned in sewage.

A nurse at the school tried to revive the child.

Hasselbeck remembers the scene vividly. He remembers the chaos and a sense of utter despair. Overwhelmed by the scene, he vomited.

“We had a refection that evening,” Dziak says. “There wasn’t a single person who didn’t have tears.”

A month after arriving home in Boston, Hasselbeck got sick with hepatitis A, which he probably got from drinking the water in Jamaica. He was hospitalized for six days, his weight dropped from 215 to 185, and he missed spring football practice. All 100 of his teammates had to get hepatitis shots.

Jaundiced – his eyes and skin yello – he lay in the hospital, waiting for his release and wondering about his future in football.”

“But I never really thought, ‘Why me?'” says Hasselbeck, who was one of four students on the trip who contracted hepatitis. “I thought, ‘This is nothing compared to what the lepers in Jamaica deal with.’ And they had so much joy in their hearts because of the Lord, despite their circumstances.”

It was then that Hasselbeck made a promise to God.

“While lying in that hospital bed, I said a prayer,” Hasselbeck says. “I said ‘Dear God, I apologize for not using my health and athletic ability You’ve give me to the fullest.’ I made a promise that when I got better and I knew I’d get better, I was going to try as hard as I can all the time.”

Matt Hasselbeck at Seahawks training camp in August of 2010. (Photo Courtesy: jc.winkler (Flickr) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

“I made a lot of excuses why I wasn’t playing,” says Hasselbeck, who was a seldom-used backup his freshman and sophomore seasons. “All of the time somebody else was the problem. Not me.”

It was the coach’s fault he wasn’t starting. Or a wide receiver’s fault. Or the linemen’s fault.

“I also think I didn’t work as hard as I needed because I think that gave me an out if I wasn’t successful,” Hasselbeck says. “If I wasn’t named the starting quarterback it was, well, I didn’t try that hard anyway.”

All that changed with his prayer in the hospital.

Hasselbeck remembers vomiting after running sprints by himself at a track not far from his home.

“I was doing this for an audience of One, now,” Hasselbeck says. “I’m playing for the Person who created me. And I’m to make Him proud and to not waste this ability He’s given me.”

The results were dynamic. He went from being a forgotten backup to the starter.

“I was a terrible player who couldn’t even break the top four,” Hasselbeck says. “I became the guy who became the starting quarterback, who played well, who made the NFL practice squad with Green Bay, who moved up to the backup spot, and who became the starter.”

It was a long hard road, directed by one moment.

“I really think it all started with that lesson I learned in Jamaica.” Hasselbeck says.

Hasselbeck didn’t begin the season as the starter his junior year at Boston College. But he came in off the bench with his team trailing Hawaii and led the Eagles to a touchdown and a field goal as time expired for the win. He started the remaining 10 games that season and started his entire senior year to become the school’s fifth all-time leading passer and a sixth-round draft pick by the Green Bay Packers.

He returned to Jamaica with a better appreciation for life and for the things he had. Simple things like running water, a light switch, and windows.

“When I got back home, I felt so guilty” he says. “I felt guilty every time I brushed my teeth and left the water running. I felt guilty about complaining about anything.”

Hasselbeck was an unexpected member on the trip to Jamaica. His football coaches at Boston College objected, saying that making trips like that wasn’t why he came to school. He became the first football player to make the trip. He wasn’t the last. His brother, Tim, now a quarterback with the New York Giants, later followed, along with other football players.

When Hasselbeck packed his bags and boarded the plane heading for Jamaica, he left with the sense of being a provider. He was going with a mission – to help.

Instead, he got an unexpected surprise.

“We all went down there to help them,” Hasselbeck says. “We thought we can help them because we’ve got money and the time. When I got down there, I realized, ‘Yeah, we helped them a little. But they helped us.’ They helped me more than I ever helped them. I thought I was giving, but I was receiving.”

The return wasn’t monetary. It was seeing the joy that shined in the lives of people like McVee.

“I thought Matt might have regretted going to Jamaica, “Dziak say. “But he never had a sense that he wished he hadn’t gone. You sometimes wonder why God puts you in places or sends you to places. But there was always this sense that he gained so much from it.”

After the trip, students on the outreach wrote their thoughts in a log book. Hasselbeck wrote: “We came down with money, food, supplies to your lives. You’ve given back to me a hundred times what I could have given you.”

When Dziak visited Hasselbeck in the hospital, he asked the future All-Pro quarterback if he regretted going.

“He said no and he’d do it all over again” Dziak says.

Dziak doesn’t think fame and wealth have changed Hasselbeck’s “God-centeredness.”

“That’s who he is and who he’ll always be,” Dziak says. “Even as aggressive as he is on the field, get him off the field and there’s a real gentleness and a real spirit about him – you always feel that God is present there.”

Matt Hasselbeck featured in the January-February 2007 edition of Sports Spectrum Magazine.