There’s a stairwell that leads to a lonely apartment on Hinesley Avenue, down the street from Hinkle Fieldhouse.

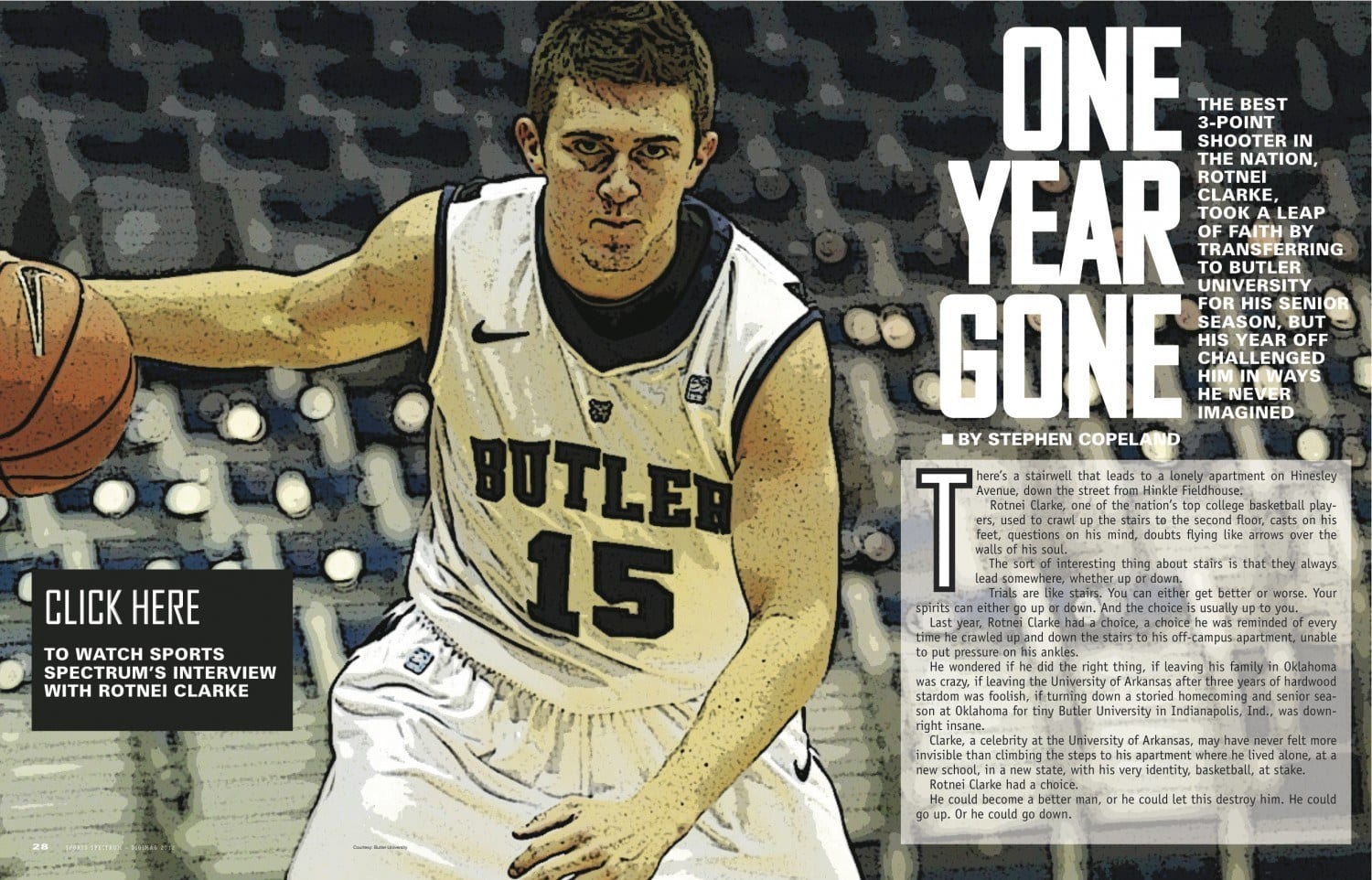

Rotnei Clarke, one of the nation’s top college basketball players, used to crawl up the stairs to the second floor, casts on his feet, questions on his mind, doubts flying like arrows over the walls of his soul.

The sort of interesting thing about stairs is that they always lead somewhere, whether up or down.

Trials are like stairs. You can either get better or worse. Your spirits can either go up or down. And the choice is usually up to you.

Last year, Rotnei Clarke had a choice, a choice he was reminded of every time he crawled up and down the stairs to his off-campus apartment, unable to put pressure on his ankles.

He wondered if he did the right thing, if leaving his family in Oklahoma was crazy, if leaving the University of Arkansas after three years of hardwood stardom was foolish, if turning down a storied homecoming and senior season at Oklahoma for tiny Butler University in Indianapolis, Ind., was downright insane.

Clarke, a celebrity at the University of Arkansas, may have never felt more invisible than climbing the steps to his apartment where he lived alone, at a new school, in a new state, with his very identity, basketball, at stake.

Rotnei Clarke had a choice.

He could become a better man, or he could let this destroy him. He could go up. Or he could go down.

So Long, Arkansas

Rotnei Clarke’s journey to Butler University is about as unimaginable as the Bulldogs’ back-to-back Final Four appearances.

No one goes to school expecting to transfer, and Clarke was no exception. You expect to be there for four years, at least—maybe more if you live in a fraternity and have rich parents.

Clarke played at the University of Arkansas for three years. That’s right, three years. When you transfer with only a year remaining, people look at you like you’re building an ark, like you’re crazy.

No one wanted Clarke to leave. Arkansas actually wouldn’t even grant his initial request to be released, which is almost unheard of. But when you talk to Clarke—a polite, clean-cut country boy who has mastered the art of the faux hawk and is obsessed with Christian rap—you can kind of understand why, why they’d want to keep him, cage him, control him. He’s not easy to replace.

At the University of Arkansas, Clarke was treated like a god. The six-foot sharp shooter could play basketball. His sophomore season, ESPN’s Andy Katz named him the best shooter in the country. The first game of his junior season, Clarke scored 51 points (school record) and nailed 13 3-pointers (SEC record) against Alcorn State.

Short. White. Shooter from a small town. In a way, he was very Hoosier.

Also, on a Razorback team with many off-the-court issues, Clarke talked the talk, wore “Jesus” on his sleeve, and was the face of the program. He was a constant glimmer of hope for nettled Razorback fans wounded by negative press. He was a role model, a light in the darkness.

Character. Commitment. Selflessness. In a way, he was very Butler.

Transferring from Arkansas would mean sitting out a season to follow NCAA rules, which made his decision to depart even more desperate. But he needed out. His coach, John Pelphrey, was fired after finishing 18-13 in the 2010-11 season, and the year before, five of Clarke’s teammates were suspended at the start of the season for various disciplinary issues, one of which were rape allegations involving three players at a party, causing them to only dress nine players which included an Arkansas golfer and former football player.

“I just knew I was supposed to get out of there,” Clarke says. “I especially knew it when Coach Pelphrey got fired. I just didn’t feel comfortable with it at all. But it was hard because I dedicated so much to that program.”

With the best shooter in the nation back on the market, some interesting storylines began to develop, and Clarke’s final year of eligibility was shaping up to make a nice homecoming to the University of Oklahoma, the state where he led Verdigris High School to its first Class 3A state championship and became the state’s leading point scorer with 3,758 career points (33.2 points per game).

But Oklahoma was dealing with its own allegations, and Sooner or later, Brad Stevens and the Butler Bulldogs entered the picture.

“It was the last place I thought I would be, honestly,” Clarke says, his Oklahoma accent prevalent, something that has to make mid-west Butler girls blush and crumble. “In my high school process of recruiting, I was patient that if people wanted me enough, they’d keep on going after me. It was the same thing with Butler. I didn’t really have to make a decision. I just knew it was right.”

And thus began the most trying year of Clarke’s career.

Removed

The transition wasn’t difficult because Butler is nine and a half hours from home, or because it has harsh, gray winters that force you to see the world in all of its cruelty, or because it has basketball facilities as old as Betty White.

It was difficult because of what unraveled, difficult because life is only a moment away from spiraling out of control. Not because of Butler.

Clarke went to Butler because it felt right. At Arkansas, where coaches were getting fired and teammates faced felonies, Butler filled a void. Stevens and the Bulldogs did things the right way—the Butler Way—and it resulted in two back-to-back national championship appearances. Clarke fit the prototype. He was very Butler.

He knew the transition would have its challenges. He was leaving family, friends and an institution that treated him like Justin Bieber.

The toughest part was not being able to travel with the team, his friends, because he had to sit out a year. On those lonely, winter nights, he would escape to a dimly lit Hinkle Fieldhouse, shoot hundreds of 3-pointers, and imagine his comeback. He was sitting out a year, but he still had basketball. He still had Hinkle.

That’s when it was taken away.

For three years at Arkansas, Clarke says he would go into the training room every day and complain about his ankles. They caused pain every game, and he was losing his flexibility. They took x-rays. They took MRIs. Nothing.

When he arrived at Butler, he says the trainer took one look at it and, from experience, knew exactly what it was: a bone going across both of his ankles, something he had been born with. It required minor surgery but four months of recovery.

Clarke, who had never even sat out two weeks of basketball, saw the sport stripped from his life for the first time. Not only was he sitting out a season, but he could also no longer practice.

The worst, perhaps, was that he could no longer distract himself while his team was on the road. His late-night shooting sessions at Hinkle were over.

Instead, he was wheeling around campus and climbing stairs.

Believability

The sort of interesting thing about stairs is that they always lead somewhere, whether up or down.

To many, Clarke had every reason to be upset, every reason to let his hope fail, every reason to doubt his Christian faith and the belief that God is in control of his life. He left his family, his friends, and a school that loved him. He took a risk because he believed God wanted him to. He took a risk for one season of eligibility because he believed God wanted him to. And yet this is what he received, the possibility that his basketball career was already over and he may never be the same basketball player again.

“There was a time I definitely doubted God,” Clarke says candidly. “I left my family. I left my friends. I left diehard fans who just wanted to see me succeed. What I left was a comfort zone—I dove out of my comfort zone—but I see how much it has changed me as a person.”

There were nights that Clarke admittedly laid in his bed and cried. His mother visited him one weekend and started bawling when she left. “She hated seeing me like that,” Clarke says. “It was the ultimate low for me.”

Risks can be maddening because they don’t necessarily grant you anything. Job faced trial after trial, loss after loss. Peter followed Jesus and was crucified upside down. Paul followed Jesus and got rocks hurled at him. With each step comes the challenge of crawling up another one. It’s called “life.”

“That’s a mistake a lot of us make,” Clarke says. “It’s easy to praise God because I’ve had a great day or a great practice or a great game. It’s easy to praise him in success, but when you are really going through a struggle or something really tough in your life, I feel like I blame God. But this made me realized that if basketball is taken away from me, I know I still have my relationship with Him. I can still find Him. I can still seek Him. He’s going to be there for me no matter what—when basketball isn’t.”

Trials, perhaps, challenge the very consistency of our souls.

And if there’s a word that describes Clarke, it’s that: consistent.

Back in high school, Clarke remembers reading his Bible on the way to the state tournament, like he usually did.

“Come here,” a teammate said.

Clarke went and sat by him. “I want to read with you,” his teammate continued.

Situations like that weren’t unusual throughout high school. People noticed the way Clarke lived. He wasn’t a Bible thumper. He just lived out what he believed. And people—like his teammates—acknowledged, even admired, his consistency.

Like the time Clarke was sitting in his high school computer class, thinking about ways he could impact lives, and decided to write a letter—letters that were placed in every visiting team’s locker room at a tournament Verdigris was hosting. The letter explained what Jesus meant to him, sited Bible verses, and had “Rotnei Clarke” at the top. Everyone knew who Rotnei Clarke was. He was one of the best players in the state.

“Hey,” an opposing player said to Clarke in the middle of a game. “Thanks. I really appreciated you putting that in the locker room.”

Or the time Verdigris, a public high school, won its first ever state title Clarke’s senior year, and Clarke led prayer in front of a 14,000-person crowd as every player and coach knelt at center court.

Clarke had a consistent zeal about his faith that made what he believed, well, believable. His teammate asked to read with him. The opposing player thanked him in the middle of a game. The whole staff looked to him to pray.

Nothing changed when Clarke went off to college.

“I remember people saying, ‘He may be a nice kid and do the right things now, but when he gets to college, he’s gonna be crazy.’ I would just laugh at that,” Clarke says.

Clarke spoke in the Fayetteville area numerous times about his faith and would even drive 2-3 hours sometimes to speak at churches and basketball events. “I enjoy sharing my story,” he says.

He does. Clarke talks about Jesus more freely than he talks about his accolades. He is more concerned with souls than self. It’s kind of weird, really. At a young age, he just got it. While his teammates at Verdigris were kings of the halls, he was typing up a letter in his computer class. When teammates were partying at Arkansas, he was driving three hours to a speaking engagement to talk about some dude he’s obsessed with named Jesus.

And that’s what makes his phase of life at Butler University so interesting. Basketball—the very core of his being, his identity, something he had always had—was stripped, challenging the consistency of his soul. Challenging the strength of his identity.

Stairs and Springtime

There are few things more beautiful than Butler in the spring. Everything is better. The sun that beams through Hinkle’s trademark windows is a warmer sun. The white buildings around campus emerge like a painting when not disguised by snow. The campus comes alive again. It’s reborn.

It’s a refreshing reminder that, even after a bitter winter, life is still good. Seasons, after all, are only phases of weather, with positives about each one.

Last spring, Clarke was wheeling around campus when another student in a wheelchair came up to him. He could tell she had been bound to the wheelchair her entire life. She looked at him, smiling. “Wanna race?” she laughed.

He laughed, too.

Then he thought about how beautiful life was. She was in a wheelchair, and she didn’t feel sorry for herself. She could smile. Why couldn’t he?

“It says in the Bible that if you diligently seek Him, you will be rewarded,” Clarke says. “And it was hard at first with basketball being taken away from me because I was in so much doubt. (I’d wonder,) ‘Did I make the right decision? Is all this supposed to be happening?’ But it really put things into perspective on how important life is and just enjoying what is given to you.”

Life is difficult, but Clarke allowed his mind to climb upward, not downward. He got better. Not bitter. And now, the 63rd best player in the country, according to CBS Sports, is back, feeling better than he’s ever felt.

“I was joking with my dad the other day,” Clarke says, “and we were talking about how I’m just going to be bouncing off the walls when I finally get out there and play a game again.”

Clarke tries not to change with the wind, with the seasons. A follower of God who only follows sometimes, or when he or she feels like it, really isn’t a follower at all. Those people are just fickle participants. Clarke has a consistency about him that makes what he believes believable.

“I was able to find my identity,” Clarke says, “and I knew that if I didn’t have basketball I was going to be okay because I would still have my relationship with Christ.”

One year gone, and he is better for it.

By Stephen Copeland

Stephen Copeland is a staff writer at Sports Spectrum magazine.