If you could have stood in the locker room before the fight, you would have thought an army was about to charge into battle. The energy gave you chills. The noise made your head throb.

As Robert Guerrero’s team, family and friends gathered around him, howling and chanting, Bob Santos stood quietly, questioning their naivety, nervously wondering if this would go down as the biggest mistake of Robert Guerrero’s career.

It’s not that Santos didn’t believe in Guerrero. He had managed the 29-year-old Mexican American from Gilroy, Calif., since he was 17—no one believed in him more—but what they were about to do was unheard of.

After all, Guerrero had been out of boxing for 15 months because of a busted shoulder; and he had moved up two weight classes, from a 135-pound lightweight to a 147-pound welterweight, a division loaded with boxing’s best fighters.

The only boxer in recent history to make a jump as radical as Guerrero, according to Santos, was “Sugar” Shane Mosley back in 2003 when he fought Oscar De La Hoya; but it was later revealed Mosley took performance-enhancing drugs to do so. Even when Manny Pacquiao climbed to the welterweight division, he didn’t fight full welterweights; he fought guys who also climbed from smaller weight classes; he eased into it. Henry Armstrong is known for his multi-weight class dominance, but heck, his prime was in the 1930s.

Yet here was Guerrero, fighting a full welterweight in prized Turkish fighter Selcuk Aydin—with no glove specifications as Floyd Mayweather Jr. forces upon his opponents, no catch-weight specifications, and no tune-up fight.

The boxing world—the people who really understood boxing—grasped the severity of Guerrero’s fight with Aydin. Even boxing legend and 10-time world champion De La Hoya approached Guerrero before the fight and asked, “Man, don’t you think you need a tune up?” to which Guerrero confidently replied, his Spanish accent prevalent, “I don’t need tune ups.”

Guerrero’s nickname is “The Ghost,” but on that evening, Santos looked like one. “That was the most nervous I was his entire career,” says Santos, a boxing encyclopedia who speaks with passion reminiscent of Mickey Goldmill from the Rocky film series. “I was nervous from the simple standpoint that I had been in the sport long enough to know it is not normal to jump up two weight classes, let alone after a year and a half layoff, let alone with no tune up. I was very concerned, and I didn’t know if he could take a punch at his weight.”

A lopsided defeat, Santos believed, would make them look like “the biggest idiots the sport had ever known.” But the coming battle was inevitable; they had signed the fight; there was no turning back; and Guerrero stood in the middle of a raucous locker room scene—pre-fight pandemonium.

“It’s Guerrero time!” someone cried. “It’s Guerrero time!”

Others joined in, the cry growing louder and louder, intensifying with the seconds of the approaching brawl. “It’s Guerrero time! It’s Guerrero time! It’s Guerrero time!”

“No,” Guerrero said sternly, the shrill of his tone piercing the commotion.

The locker room fell silent.

“It’s Jesus Christ time,” he said, his voice loud enough to trump gunshots, sharp enough to bring a child to tears. “It’s God’s time.”

Santos says there was a fire in Guerrero’s eyes.

“At that point,” Santos says, “I said to myself, ‘He is not getting beat tonight. He is NOT getting beat tonight.’”

And thus began Guerrero’s journey to Mayweather.

Guerrero walked through the tunnel…to the ring…leaving a silent locker room behind him.

_____________________________________________________

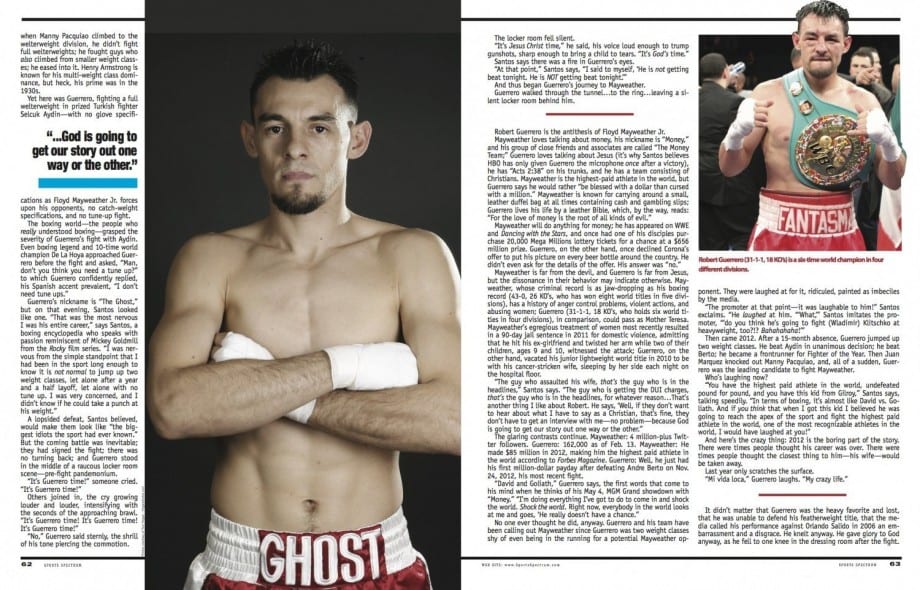

Robert Guerrero is the antithesis of Floyd Mayweather Jr.

Mayweather loves talking about money, his nickname is “Money,” and his group of close friends and associates are called “The Money Team;” Guerrero loves talking about Jesus (it’s why Santos believes HBO has only given Guerrero the microphone once after a victory), he has “Acts 2:38” on his trunks, and he has a team consisting of Christians. Mayweather is the highest-paid athlete in the world, but Guerrero says he would rather “be blessed with a dollar than cursed with a million.” Mayweather is known for carrying around a small, leather duffel bag at all times containing cash and gambling slips; Guerrero lives his life by a leather Bible, which, by the way, reads: “For the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil.”

Mayweather will do anything for money; he has appeared on WWE and Dancing with the Stars, and once had one of his disciples purchase 20,000 Mega Millions lottery tickets for a chance at a $656 million prize. Guerrero, on the other hand, once declined Corona’s offer to put his picture on every beer bottle around the country. He didn’t even ask for the details of the offer. His answer was “no.”

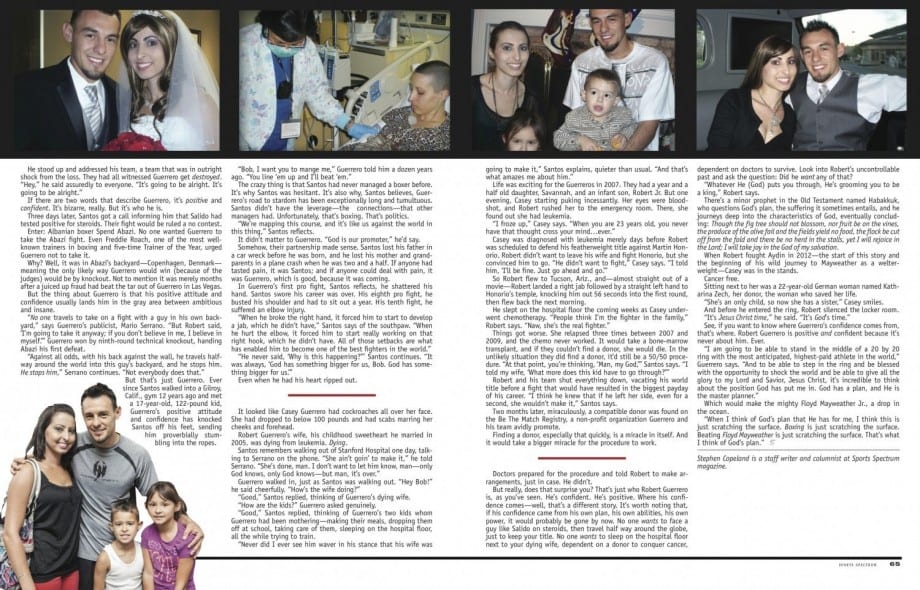

Mayweather is far from the devil, and Guerrero is far from Jesus, but the dissonance in their behavior may indicate otherwise. Mayweather, whose criminal record is as jaw-dropping as his boxing record (43-0, 26 KO’s, who has won eight world titles in five divisions), has a history of anger control problems, violent actions, and abusing women; Guerrero (31-1-1, 18 KO’s, who holds six world titles in four divisions), in comparison, could pass as Mother Teresa. Mayweather’s egregious treatment of women most recently resulted in a 90-day jail sentence in 2011 for domestic violence, admitting that he hit his ex-girlfriend and twisted her arm while two of their children, ages 9 and 10, witnessed the attack; Guerrero, on the other hand, vacated his junior lightweight world title in 2010 to be with his cancer-stricken wife, sleeping by her side each night on the hospital floor.

“The guy who assaulted his wife, that’s the guy who is in the headlines,” Santos says. “The guy who is getting the DUI charges, that’s the guy who is in the headlines, for whatever reason…That’s another thing I like about Robert. He says, ‘Well, if they don’t want to hear about what I have to say as a Christian, that’s fine, they don’t have to get an interview with me—no problem—because God is going to get our story out one way or the other.”

The glaring contrasts continue. Mayweather: 4 million-plus Twitter followers. Guerrero: 96,000 as of May. Mayweather: He made $85 million in 2012, making him the highest paid athlete in the world according to Forbes Magazine. Guerrero: Well, he just had his first million-dollar payday after defeating Andre Berto on Nov. 24, 2012, his most recent fight.

“David and Goliath,” Guerrero says, the first words that come to his mind when he thinks of his May 4, MGM Grand showdown with “Money.” “I’m doing everything I’ve got to do to come in and shock the world. Shock the world. Right now, everybody in the world looks at me and goes, ‘He really doesn’t have a chance.”

No one ever thought he did, anyway. Guerrero and his team have been calling out Mayweather since Guerrero was two weight classes shy of even being in the running for a potential Mayweather opponent. They were laughed at for it, ridiculed, painted as imbeciles by the media.

“The promoter at that point—it was laughable to him!” Santos exclaims. “He laughed at him. “‘What,’” Santos imitates the promoter, “‘do you think he’s going to fight (Wladimir) Klitschko at heavyweight, too?!? Bahahahaha!’”

Then came 2012. After a 15-month absence, Guerrero jumped up two weight classes. He beat Aydin in unanimous decision; he beat Berto; he became a frontrunner for Fighter of the Year. Then Juan Marquez knocked out Manny Pacquiao, and, all of a sudden, Guerrero was the leading candidate to fight Mayweather.

Who’s laughing now?

“You have the highest paid athlete in the world, undefeated pound for pound, and you have this kid from Gilroy,” Santos says, talking speedily. “In terms of boxing, it’s almost like David vs. Goliath. And if you think that when I got this kid I believed he was going to reach the apex of the sport and fight the highest paid athlete in the world, one of the most recognizable athletes in the world, I would have laughed at you!”

And here’s the crazy thing: 2012 is the boring part of the story. There were times people thought his career was over. There were times people thought the closest thing to him—his wife—would be taken away.

Last year only scratches the surface.

“Mi vida loca,” Guerrero laughs. “My crazy life.”

_____________________________________________________

It didn’t matter that Guerrero was the heavy favorite and lost, that he was unable to defend his featherweight title, that the media called his performance against Orlando Salido in 2006 an embarrassment and a disgrace. He knelt anyway. He gave glory to God anyway, as he fell to one knee in the dressing room after the fight.

He stood up and addressed his team, a team that was in outright shock from the loss. They had all witnessed Guerrero get destroyed. “Hey,” he said assuredly to everyone. “It’s going to be alright. It’s going to be alright.”

If there are two words that describe Guerrero, it’s positive and confident. It’s bizarre, really. But it’s who he is.

Three days later, Santos got a call informing him that Salido had tested positive for steroids. Their fight would be ruled a no contest.

Enter: Albanian boxer Spend Abazi. No one wanted Guerrero to take the Abazi fight. Even Freddie Roach, one of the most well-known trainers in boxing and five-time Trainer of the Year, urged Guerrero not to take it.

Why? Well, it was in Abazi’s backyard—Copenhagen, Denmark—meaning the only likely way Guerrero would win (because of the judges) would be by knockout. Not to mention it was merely months after a juiced up fraud had beat the tar out of Guerrero in Las Vegas.

But the thing about Guerrero is that his positive attitude and confidence usually lands him in the gray area between ambitious and insane.

“No one travels to take on a fight with a guy in his own backyard,” says Guerrero’s publicist, Mario Serrano. “But Robert said, ‘I’m going to take it anyway; if you don’t believe in me, I believe in myself.’” Guerrero won by ninth-round technical knockout, handing Abazi his first defeat.

“Against all odds, with his back against the wall, he travels halfway around the world into this guy’s backyard, and he stops him. He stops him,” Serrano continues. “Not everybody does that.”

But that’s just Guerrero. Ever since Santos walked into a Gilroy, Calif., gym 12 years ago and met a 17-year-old, 122-pound kid, Guerrero’s positive attitude and confidence has knocked Santos off his feet, sending him proverbially stumbling into the ropes.

“Bob, I want you to manage me,” Guerrero told him a dozen years ago. “You line ‘em up and I’ll beat ‘em.”

The crazy thing is that Santos had never managed a boxer before. It’s why Santos was hesitant. It’s also why, Santos believes, Guerrero’s road to stardom has been exceptionally long and tumultuous. Santos didn’t have the leverage—the connections—that other managers had. Unfortunately, that’s boxing. That’s politics.

“We’re mapping this course, and it’s like us against the world in this thing,” Santos reflects.

It didn’t matter to Guerrero. “God is our promoter,” he’d say.

Somehow, their partnership made sense. Santos lost his father in a car wreck before he was born, and he lost his mother and grandparents in a plane crash when he was two and a half. If anyone had tasted pain, it was Santos; and if anyone could deal with pain, it was Guerrero, which is good, because it was coming.

In Guerrero’s first pro fight, Santos reflects, he shattered his hand. Santos swore his career was over. His eighth pro fight, he busted his shoulder and had to sit out a year. His tenth fight, he suffered an elbow injury.

“When he broke the right hand, it forced him to start to develop a jab, which he didn’t have,” Santos says of the southpaw. “When he hurt the elbow, it forced him to start really working on that right hook, which he didn’t have. All of those setbacks are what has enabled him to become one of the best fighters in the world.”

“He never said, ‘Why is this happening?’” Santos continues. “It was always, ‘God has something bigger for us, Bob. God has something bigger for us.’”

Even when he had his heart ripped out.

_____________________________________________________

It looked like Casey Guerrero had cockroaches all over her face. She had dropped to below 100 pounds and had scabs marring her cheeks and forehead.

Robert Guerrero’s wife, his childhood sweetheart he married in 2005, was dying from leukemia. Dying.

Santos remembers walking out of Stanford Hospital one day, talking to Serrano on the phone. “She ain’t goin’ to make it,” he told Serrano. “She’s done, man. I don’t want to let him know, man—only God knows, only God knows—but man, it’s over.”

Guerrero walked in, just as Santos was walking out. “Hey Bob!” he said cheerfully. “How’s the wife doing?”

“Good,” Santos replied, thinking of Guerrero’s dying wife.

“How are the kids?” Guerrero asked genuinely.

“Good,” Santos replied, thinking of Guerrero’s two kids whom Guerrero had been mothering—making their meals, dropping them off at school, taking care of them, sleeping on the hospital floor, all the while trying to train.

“Never did I ever see him waver in his stance that his wife was going to make it,” Santos explains, quieter than usual. “And that’s what amazes me about him.”

Life was exciting for the Guerreros in 2007. They had a year and a half old daughter, Savannah, and an infant son, Robert Jr. But one evening, Casey starting puking incessantly. Her eyes were bloodshot, and Robert rushed her to the emergency room. There, she found out she had leukemia.

“I froze up,” Casey says. “When you are 23 years old, you never have that thought cross your mind…ever.”

Casey was diagnosed with leukemia merely days before Robert was scheduled to defend his featherweight title against Martin Honorio. Robert didn’t want to leave his wife and fight Honorio, but she convinced him to go. “He didn’t want to fight,” Casey says. “I told him, ‘I’ll be fine. Just go ahead and go.’”

So Robert flew to Tucson, Ariz., and—almost straight out of a movie—Robert landed a right jab followed by a straight left hand to Honorio’s temple, knocking him out 56 seconds into the first round, then flew back the next morning.

He slept on the hospital floor the coming weeks as Casey underwent chemotherapy. “People think I’m the fighter in the family,” Robert says. “Naw, she’s the real fighter.”

Things got worse. She relapsed three times between 2007 and 2009, and the chemo never worked. It would take a bone-marrow transplant, and if they couldn’t find a donor, she would die. In the unlikely situation they did find a donor, it’d still be a 50/50 procedure. “At that point, you’re thinking, ‘Man, my God,’” Santos says. “I told my wife, ‘What more does this kid have to go through?’”

Robert and his team shut everything down, vacating his world title before a fight that would have resulted in the biggest payday of his career. “I think he knew that if he left her side, even for a second, she wouldn’t make it,” Santos says.

Two months later, miraculously, a compatible donor was found on the Be The Match Registry, a non-profit organization Guerrero and his team avidly promote.

Finding a donor, especially that quickly, is a miracle in itself. And it would take a bigger miracle for the procedure to work.

_____________________________________________________

Doctors prepared for the procedure and told Robert to make arrangements, just in case. He didn’t.

But really, does that surprise you? That’s just who Robert Guerrero is, as you’ve seen. He’s confident. He’s positive. Where his confidence comes—well, that’s a different story. It’s worth noting that, if his confidence came from his own plan, his own abilities, his own power, it would probably be gone by now. No one wants to face a guy like Salido on steroids, then travel half way around the globe, just to keep your title. No one wants to sleep on the hospital floor next to your dying wife, dependent on a donor to conquer cancer, dependent on doctors to survive. Look into Robert’s uncontrollable past and ask the question: Did he want any of that?

“Whatever He (God) puts you through, He’s grooming you to be a king,” Robert says.

There’s a minor prophet in the Old Testament named Habakkuk, who questions God’s plan, the suffering it sometimes entails, and he journeys deep into the characteristics of God, eventually concluding: Though the fig tree should not blossom, nor fruit be on the vines, the produce of the olive fail and the fields yield no food, the flock be cut off from the fold and there be no herd in the stalls, yet I will rejoice in the Lord; I will take joy in the God of my salvation.

When Robert fought Aydin in 2012—the start of this story and the beginning of his wild journey to Mayweather as a welterweight—Casey was in the stands.

Cancer free.

Sitting next to her was a 22-year-old German woman named Katharina Zech, her donor, the woman who saved her life.

“She’s an only child, so now she has a sister,” Casey smiles.

And before he entered the ring, Robert silenced the locker room.

“It’s Jesus Christ time,” he said. “It’s God’s time.”

See, if you want to know where Guerrero’s confidence comes from, that’s where. Robert Guerrero is positive and confident because it’s never about him. Ever.

“I am going to be able to stand in the middle of a 20 by 20 ring with the most anticipated, highest-paid athlete in the world,” Guerrero says. “And to be able to step in the ring and be blessed with the opportunity to shock the world and be able to give all the glory to my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, it’s incredible to think about the position God has put me in. God has a plan, and He is the master planner.”

Which would make the mighty Floyd Mayweather Jr., a drop in the ocean.

“When I think of God’s plan that He has for me, I think this is just scratching the surface. Boxing is just scratching the surface. Beating Floyd Mayweather is just scratching the surface. That’s what I think of God’s plan.”

By Stephen Copeland

Stephen Copeland is a staff writer and columnist at Sports Spectrum magazine.