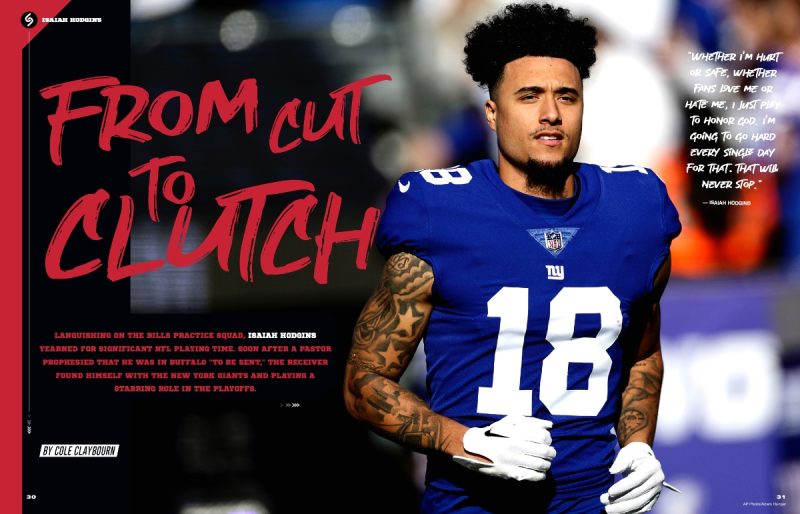

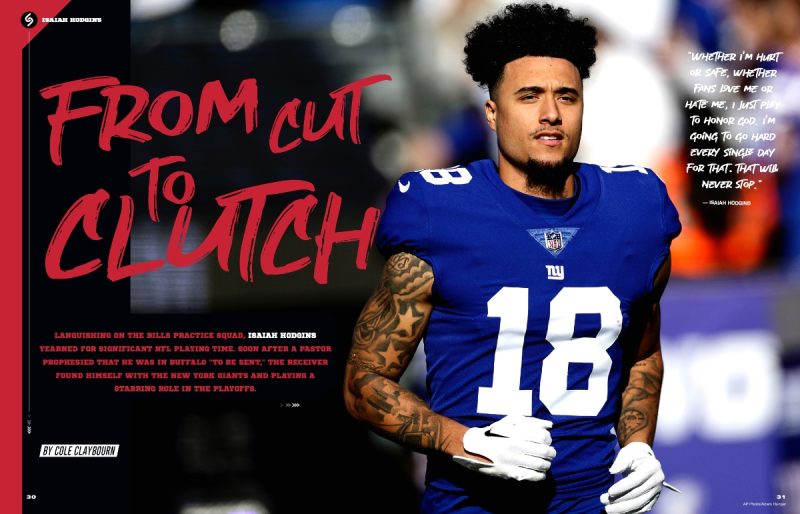

New York Giants wide receiver Isaiah Hodgins, Jan. 1, 2023. (AP Photo/Bryan Woolston)

This story appears in the Summer 2023 issue of Sports Spectrum Magazine. To read the rest of it, and for more in-depth feature stories like it, subscribe to our quarterly magazine!

Summer 2023 issue

Languishing on the Bills practice squad, Isaiah Hodgins yearned for significant NFL playing time. Soon after a pastor prophesied that he was in Buffalo “to be sent,” the receiver found himself with the New York Giants and playing a starring role in the playoffs.

***

Hodgins was just being his “stupid, energetic self.” It was two days before the New York Giants’ wild-card matchup against the Minnesota Vikings — which would be his first career NFL playoff game — and during the team’s light walkthrough he jumped up to celebrate a touchdown catch. But he landed wrong and turned his ankle. When it became black and blue and swelled up, he knew it was significant.

“I couldn’t even do a walkthrough, and then I had to get on a flight to Minnesota and it got more swollen from the flight,” Hodgins recently told Sports Spectrum. “… I felt like, ‘Dang, I’m going to let my team down.'”

Trainers went to work on his ankle day and night until the game, while Hodgins prayed fervently for healing. He told God, “If I play this game, it’s only going to be because of You, and if I make it through this game, it’s only because of You.”

It’s hard to blame Hodgins for being a little excited to make his postseason debut. A sixth-round draft pick by the Buffalo Bills in 2020, the former Oregon State standout had mostly been a practice-squad player during his short time in the NFL. When the Bills waived him this past November, the Giants claimed him the next day.

Being cut was tough, but there was at least a silver lining with his new spot. Giants head coach Brian Daboll had coached Hodgins in Buffalo as the offensive coordinator, so it wasn’t a completely unfamiliar situation for him. Daboll saw something in Hodgins that seemed to make sense for their offense, and the returns were almost immediate.

After joining the Giants, Hodgins averaged more than four catches and nearly 44 yards per game over eight games, and he hauled in four touchdown catches. He quickly became a trusted target for quarterback Daniel Jones, and in the team’s penultimate regular-season game, he caught a career-high eight passes for 89 yards and a touchdown.

With momentum heading into the playoffs, and after sitting and watching for all that time in Buffalo, Hodgins felt his chance was finally coming. But then, the ankle mishap.

“Having played Minnesota already earlier in the year (a Week 16 Giants loss in Minnesota), he knew this could be his breakout game,” said Isaiah’s father, James Hodgins, a former NFL player himself. “I think that was part of the spiritual thing about that game, knowing he had to go into it and fully trust God.”

Isaiah played in the game, just his sixth career start. And he introduced himself to the huge playoff-watching audience with a career performance: 105 receiving yards on eight catches, including a touchdown reception, all of which helped the sixth-seeded Giants score a 31-24 road victory over the third-seeded Vikings.

New York Giants WR Isaiah Hodgins catches a touchdown pass in the playoffs, Jan. 15, 2023. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

With each completed catch, and especially after the touchdown, Isaiah’s mind became less focused on the pain.

“I just started to really sit there on the bench and be like, ‘God is really working right now,'” he said. “‘He’s really bringing me through this. My foot is in serious pain and I would not be able to do this without God.'”

Without question, the stellar showing instantly went down as the best game of Hodgins’ career — and he probably shouldn’t have even been playing. He didn’t know until after the win that the injury was worse than he’d imagined. What he thought may have been a sprained ankle actually turned out to be a fracture.

All things considered, it was an objectively amazing performance. But if there’s one thing Isaiah Hodgins wants people to know about him, it’s that he’s not interested in basking in the praise. It’s not that he doesn’t appreciate it, but the 24-year-old would rather his success reflect Whom it comes from.

“A reporter asked me after the game, ‘A couple of months ago you were on the practice squad and now you’re sitting here catching a hundred yards in a playoff game,’ and I’m just like, ‘That’s God,'” Hodgins said. “That’s just how quick He could work, His plan coming to fruition, and it’s nothing else. Obviously I had to work hard and stay with it, but that’s just God and how He works and His plans for my life. So it has been awesome to see it all unfold.”

“I just started to really sit there on the bench and be like, ‘God is really working right now. He’s really bringing me through this. My foot is in serious pain and I would not be able to do this without God.'” — Isaiah Hodgins

***

James Hodgins played seven years in the NFL and was a member of the Super Bowl XXXIV-winning St. Louis Rams in 1999. He knows what it takes to play and stay in the NFL. His son’s success last season wasn’t a surprise, he told Sports Spectrum. He knew Isaiah had the ability, and once he got the opportunity, it was just a matter of time.

“We were expecting God to eventually show up and there be a breakout season, we just didn’t know when,” said James, who says he’s witnessed Isaiah walking faithfully with the Lord and putting his trust in Him throughout his football journey.

The foundation of Isaiah’s faith goes all the way back to his upbringing in San Francisco’s Bay Area. James and his wife, Stephanie, had Isaiah and his siblings in church “as much as possible,” James said, regularly attending youth groups and Fellowship of Christian Athletes camps.

They eventually enrolled Isaiah at Berean Christian High School in Walnut Creek, California, which James credits for helping Isaiah deepen his relationship with God thanks to a better theological understanding of the Bible and the Christian faith. They did all they could to raise Isaiah and his siblings as Christ-followers.

“The reality is, for all of us at some point, your faith has to be your own, not your parents’,” James said. “That was always our biggest thing to both of our sons and our daughters, that you have to take this faith journey with God yourself.”

For Isaiah, that really started once he arrived at Oregon State. But it didn’t come without some hurdles. He earned a starting spot his freshman year, so he naturally became a popular guy on campus. Though he considered himself a Christian, he wasn’t reflecting it with his choices, as his weekends often included drinking alcohol and attending parties.

Then he got hurt during spring practices later that freshman year. That gave him time to reflect on his faith and relationship with God.

“That was the time I started really taking my walk seriously,” he said. “Not just on Sundays, but throughout the week. I made it a goal that I’m going to be unashamed about this. I invited players to church. I was sitting there being outspoken about my faith and doing Bible studies throughout the week and stuff that was helping me grow.”

That continued once he got to Buffalo. His presence may not have been felt on the field much, but that didn’t stop him from taking on a leadership role in the locker room. Just as he did in college, Isaiah, along with his wife, Maya, invited players to church and led Bible studies. In everything he did, he just wanted to reflect Jesus.

***

It’s been said that a tested faith is a trusted faith. As positive as Isaiah stayed while spending most of his time on the practice squad, he’s still a competitive athlete who wants to earn a chance to play. Heading into the 2022 season, he felt like he was doing that.

He put together what he thought was one of his best preseasons since he’d been in the NFL. He was making plays and putting up good numbers that showed he could produce at that level. He thought he had done enough to secure a spot on the active roster, but even if the Bills were to cut him, he felt he would warrant interest from another team.

He ended up getting cut right after the preseason and then went unclaimed. So he returned to the Bills practice squad. That felt like a “dagger,” he said.

“I had all these goals written in my notes like, ‘I’m going to get this many yards, this many touchdowns,'” he said. “We already were expecting baby No. 2, so I was like, ‘I’m going to be on the active roster. I’m going to buy a house with this money,’ and all this stuff.

“I had all these plans and God put it on a pause and I was like, ‘Dang, this is hard.’ I had all these big plans for myself that I thought were so great and God was telling me to rest and wait and continue to grow in my character, and not really worry about my circumstances other than building my character.”

Hodgins credits the Bills organization, especially team chaplain Len Vanden Bos, for the continued growth in his faith. He stayed patient and was eventually called up to the active roster in Week 5. But he still didn’t play all that much, and at the trade deadline the Bills waived him yet again.

“That’s when it was like a dagger again,” he said. “I was living on this high and then I got back low, but then through it all I was trying not to let my heart get to a resentment for God or anything, and trust what God has for me: ‘If it’s just learning how to manage money better, if You want me to grow in Buffalo more, it is what it is.'”

This time, the Giants made sure he didn’t go unclaimed.

“I had all these plans and God put it on a pause and I was like, ‘Dang, this is hard.’ I had all these big plans for myself that I thought were so great and God was telling me to rest and wait and continue to grow in my character.” — Isaiah Hodgins

***

Isaiah Hodgins (Photo by Leah Montgomery/Sports Spectrum)

A week or two prior, Hodgins attended his Buffalo church with several of his teammates. Not knowing that Isaiah or any of his teammates were professional athletes, the pastor happened to pick Isaiah out of the bunch and began to prophesy over him.

“‘Listen, you got brought here to be sent, and Buffalo isn’t your finishing place,'” Isaiah said, recounting the pastor’s words over him. “‘God is working on your character and is going to send you somewhere else.’ [The pastor] didn’t know who I was at all, and he [continued prophesying], ‘I see your face on TV, on the media, on all this stuff, but don’t let it get to your head. Use God’s platform and reach other people and help people out.'”

The pastor urged Isaiah and Maya to continue praying together because they were about to go somewhere that they’d be used by God…

This story appears in the Summer 2023 issue of Sports Spectrum Magazine. To read the rest of it, and for more in-depth feature stories like it, subscribe to our quarterly magazine!

RELATED CONTENT:

— SS PODCAST: Giants’ Isaiah Hodgins on his breakout, staying connected to Jesus

— Giants WR Isaiah Hodgins shines in playoff debut, plays to honor God

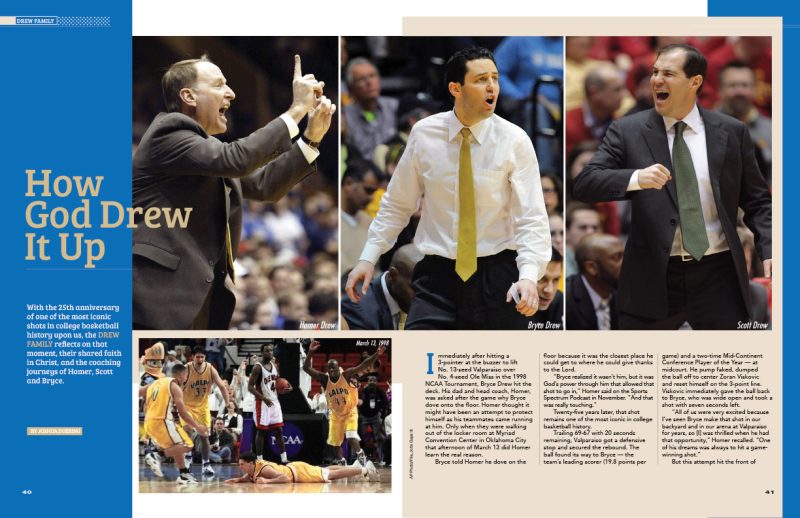

— MAGAZINE: How God Drew It Up — 25th Anniversary of Bryce Drew’s iconic shot

— MAGAZINE: New Orleans Linebacker Demario Davis Is A Spirit-Led Saint

— MAGAZINE: Alabama Quarterback Bryce Young Puts Faith Before Fame

— MAGAZINE: Cardinals’ Adam Wainwright & Wife Jenny All About Family Matters

— MAGAZINE: NC State’s Kai Crutchfield is Founded and Faithful

— MAGAZINE: Phoenix Suns Coach Monty Williams Is The Ace Of Self-Effacing

— MAGAZINE: Liberty Quarterback Malik Willis Stays Humble Amid The Hype

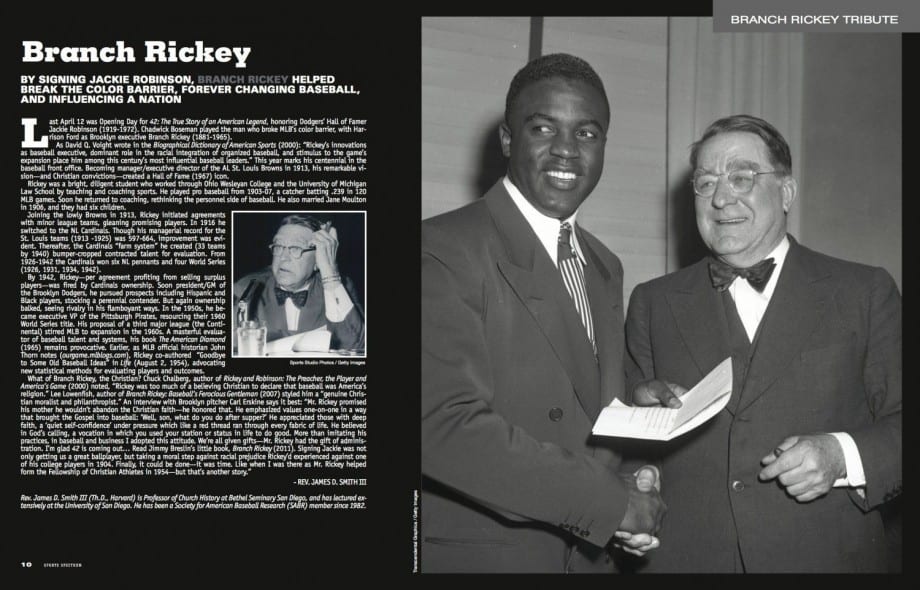

Last April 12 was Opening Day for 42: The True Story of an American Legend, honoring Dodgers’ Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson (1919-1972). Chadwick Boseman played the man who broke MLB’s color barrier, with Harrison Ford as Brooklyn executive Branch Rickey (1881-1965).

Last April 12 was Opening Day for 42: The True Story of an American Legend, honoring Dodgers’ Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson (1919-1972). Chadwick Boseman played the man who broke MLB’s color barrier, with Harrison Ford as Brooklyn executive Branch Rickey (1881-1965).