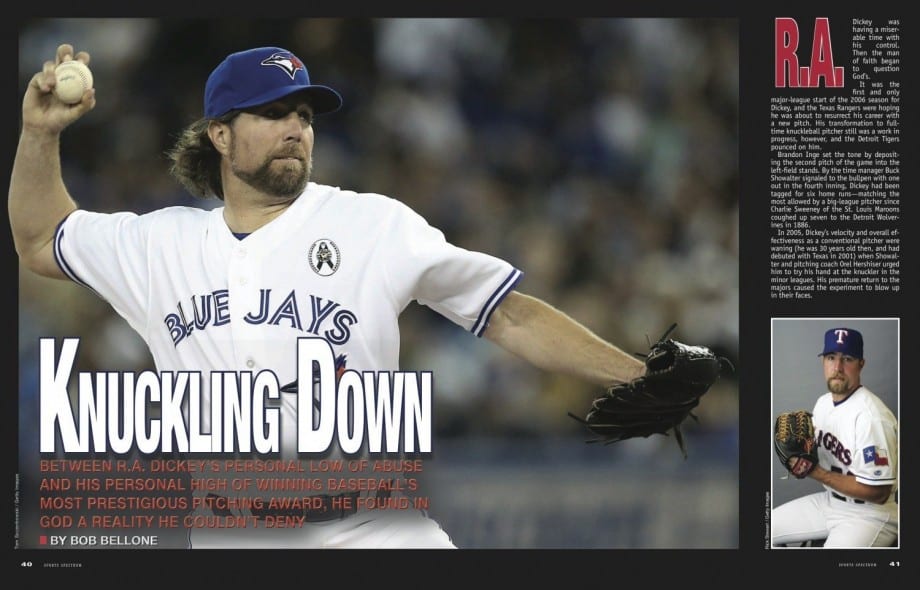

R.A. Dickey was having a miserable time with his control. Then the man of faith began to question God’s.

R.A. Dickey was having a miserable time with his control. Then the man of faith began to question God’s.

It was the first and only major-league start of the 2006 season for Dickey, and the Texas Rangers were hoping he was about to resurrect his career with a new pitch. His transformation to full-time knuckleball pitcher still was a work in progress, however, and the Detroit Tigers pounced on him.

Brandon Inge set the tone by depositing the second pitch of the game into the left-field stands. By the time manager Buck Showalter signaled to the bullpen with one out in the fourth inning, Dickey had been tagged for six home runs—matching the most allowed by a big-league pitcher since Charlie Sweeney of the St. Louis Maroons coughed up seven to the Detroit Wolverines in 1886.

In 2005, Dickey’s velocity and overall effectiveness as a conventional pitcher were waning (he was 30 years old then, and had debuted with Texas in 2001) when Showalter and pitching coach Orel Hershiser urged him to try his hand at the knuckler in the minor leagues. His premature return to the majors caused the experiment to blow up in their faces.

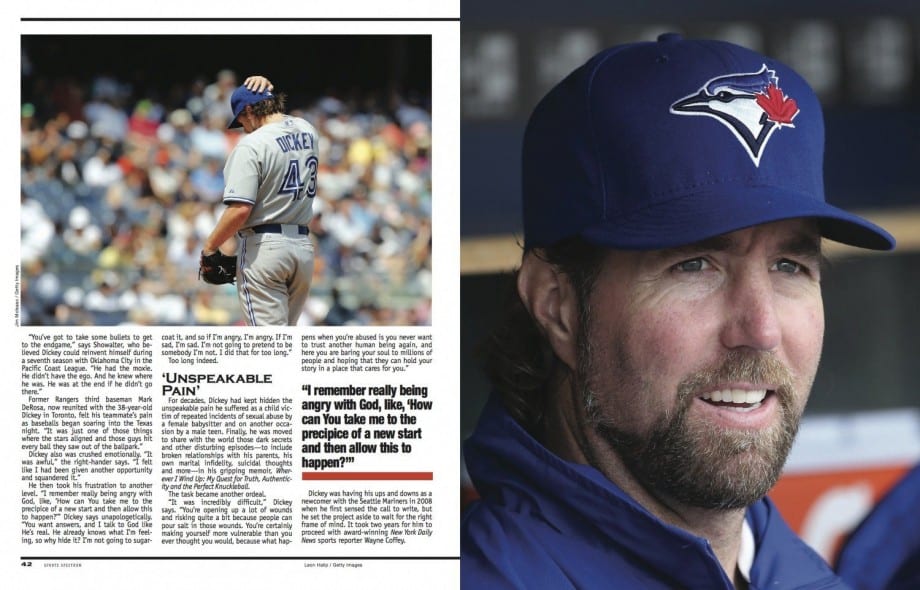

“You’ve got to take some bullets to get to the endgame,” says Showalter, who believed Dickey could reinvent himself during a seventh season with Oklahoma City in the Pacific Coast League. “He had the moxie. He didn’t have the ego. And he knew where he was. He was at the end if he didn’t go there.”

Former Rangers third baseman Mark DeRosa, now reunited with the 38-year-old Dickey in Toronto, felt his teammate’s pain as baseballs began soaring into the Texas night. “It was just one of those things where the stars aligned and those guys hit every ball they saw out of the ballpark.”

Dickey also was crushed emotionally. “It was awful,” the right-hander says. “I felt like I had been given another opportunity and squandered it.”

He then took his frustration to another level. “I remember really being angry with God, like, ‘How can You take me to the precipice of a new start and then allow this to happen?’” Dickey says unapologetically. “You want answers, and I talk to God like He’s real. He already knows what I’m feeling, so why hide it? I’m not going to sugarcoat it, and so if I’m angry, I’m angry. If I’m sad, I’m sad. I’m not going to pretend to be somebody I’m not. I did that for too long.”

Too long indeed.

‘Unspeakable Pain’

For decades, Dickey had kept hidden the unspeakable pain he suffered as a child victim of repeated incidents of sexual abuse by a female babysitter and on another occasion by a male teen. Finally, he was moved to share with the world those dark secrets and other disturbing episodes—to include broken relationships with his parents, his own marital infidelity, suicidal thoughts and more—in his gripping memoir, Wherever I Wind Up: My Quest for Truth, Authenticity and the Perfect Knuckleball.

The task became another ordeal.

“It was incredibly difficult,” Dickey says. “You’re opening up a lot of wounds and risking quite a bit because people can pour salt in those wounds. You’re certainly making yourself more vulnerable than you ever thought you would, because what happens when you’re abused is you never want to trust another human being again, and here you are baring your soul to millions of people and hoping that they can hold your story in a place that cares for you.”

Dickey was having his ups and downs as a newcomer with the Seattle Mariners in 2008 when he first sensed the call to write, but he set the project aside to wait for the right frame of mind. It took two years for him to proceed with award-winning New York Daily News sports reporter Wayne Coffey.

“I had to be okay, no matter what people thought,” Dickey says. “I had to be okay, no matter what they said. Now the blessing in that was that I have had so many people, whether it’s in fan mail or teammates or coaches or owners of teams or whatnot, come and be so encouraging. And that’s something I never expected.”

Also unforeseen was the height of Dickey’s rebound from rock bottom.

‘All on R.A.’

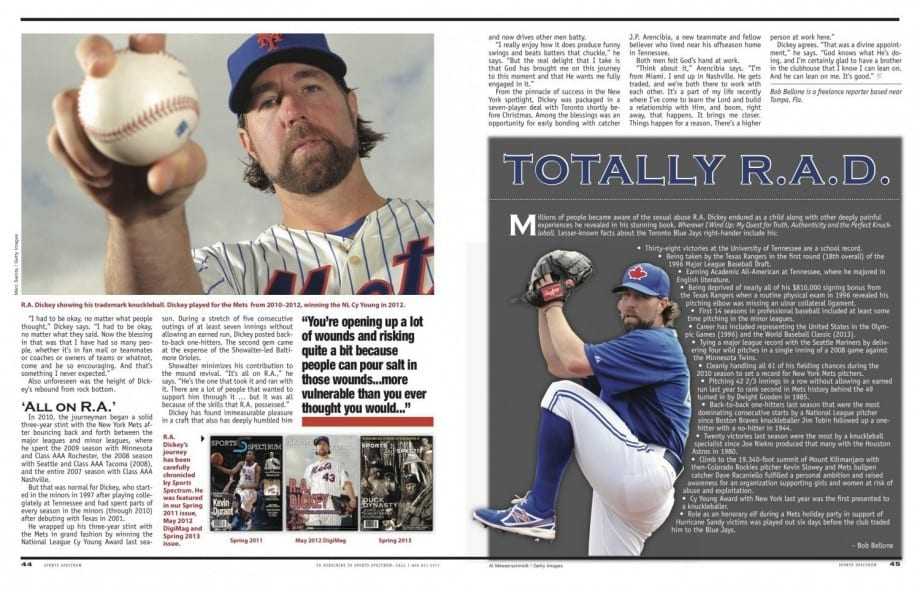

In 2010, the journeyman began a solid three-year stint with the New York Mets after bouncing back and forth between the major leagues and minor leagues, where he spent the 2009 season with Minnesota and Class AAA Rochester, the 2008 season with Seattle and Class AAA Tacoma (2008), and the entire 2007 season with Class AAA Nashville.

But that was normal for Dickey, who started in the minors in 1997 after playing collegiately at Tennessee and had spent parts of every season in the minors (through 2010) after debuting with Texas in 2001.

He wrapped up his three-year stint with the Mets in grand fashion by winning the National League Cy Young Award last season. During a stretch of five consecutive outings of at least seven innings without allowing an earned run, Dickey posted back-to-back one-hitters. The second gem came at the expense of the Showalter-led Baltimore Orioles.

Showalter minimizes his contribution to the mound revival. “It’s all on R.A.,” he says. “He’s the one that took it and ran with it. There are a lot of people that wanted to support him through it … but it was all because of the skills that R.A. possessed.”

Dickey has found immeasurable pleasure in a craft that also has deeply humbled him and now drives other men batty.

“I really enjoy how it does produce funny swings and beats batters that chuckle,” he says. “But the real delight that I take is that God has brought me on this journey to this moment and that He wants me fully engaged in it.”

From the pinnacle of success in the New York spotlight, Dickey was packaged in a seven-player deal with Toronto shortly before Christmas. Among the blessings was an opportunity for early bonding with catcher J.P. Arencibia, a new teammate and fellow believer who lived near his offseason home in Tennessee.

Both men felt God’s hand at work.

“Think about it,” Arencibia says. “I’m from Miami. I end up in Nashville. He gets traded, and we’re both there to work with each other. It’s a part of my life recently where I’ve come to learn the Lord and build a relationship with Him, and boom, right away, that happens. It brings me closer. Things happen for a reason. There’s a higher person at work here.”

Dickey agrees. “That was a divine appointment,” he says. “God knows what He’s doing, and I’m certainly glad to have a brother in the clubhouse that I know I can lean on. And he can lean on me. It’s good.”

By Bob Bellone

Bob Bellone is a freelance reporter based near Tampa, Fla.