On the surface, Herschel Walker seemingly had it all.

On the surface, Herschel Walker seemingly had it all.

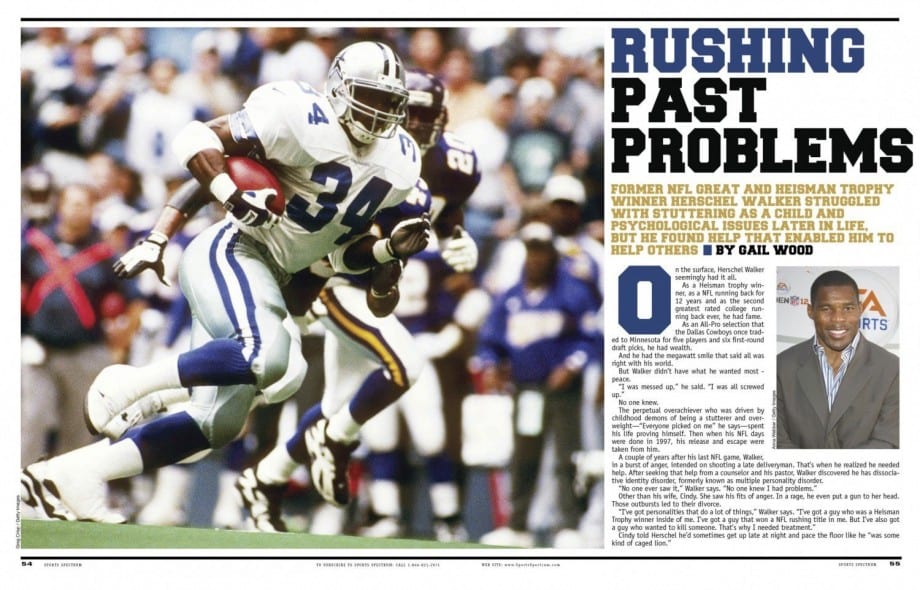

As a Heisman trophy winner, as a NFL running back for 12 years and as the second greatest rated college running back ever, he had fame.

As an All-Pro selection that the Dallas Cowboys once traded to Minnesota for five players and six first-round draft picks, he had wealth.

And he had the megawatt smile that said all was right with his world.

But Walker didn’t have what he wanted most – peace.

“I was messed up,” he said. “I was all screwed up.”

No one knew.

The perpetual overachiever who was driven by childhood demons of being a stutterer and overweight—“Everyone picked on me” he says—spent his life proving himself. Then when his NFL days were done in 1997, his release and escape were taken from him.

A couple of years after his last NFL game, Walker, in a burst of anger, intended on shooting a late deliveryman. That’s when he realized he needed help. After seeking that help from a counselor and his pastor, Walker discovered he has dissociative identity disorder, formerly known as multiple personality disorder.

“No one ever saw it,” Walker says. “No one knew I had problems.”

Other than his wife, Cindy. She saw his fits of anger. In a rage, he even put a gun to her head. Those outbursts led to their divorce.

“I’ve got personalities that do a lot of things,” Walker says. “I’ve got a guy who was a Heisman Trophy winner inside of me. I’ve got a guy that won a NFL rushing title in me. But I’ve also got a guy who wanted to kill someone. That’s why I needed treatment.”

Cindy told Herschel he’d sometimes get up late at night and pace the floor like he “was some kind of caged lion.”

“I asked her why didn’t she tell me that,” Walker says.

She did. But he wouldn’t remember.

Taking that first step, admitting he needed help, wasn’t easy.

“It was tough,” Walker says. “I was totally confused. You know, I’m Herschel Walker. I’ve won a Heisman Trophy. I’ve won a NFL rushing title. How could I have a problem?”

Finally, Walker now has that elusive peace, a result of his renewed Christian faith. His testimony today is transparent. At a recent talk to soldiers at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington, Walker began with his faith statement.

He was like a telemarketer for Christ.

“First off, I want to say that Jesus Christ is my Lord and Savior,” Walker said. “He said if I don’t acknowledge Him, He won’t acknowledge me.”

Several times during his 55-minute talk, Walker, the 1982 Heisman winner while at the University of Georgia, said, “I want you to know that Jesus loves you.”

Talking without notes, Walker gave a thumb-nail sketch of his life story, starting with when he was an overweight young boy to his days as an All-American running back for the Georgia Bulldogs to when he played in the NFL. Walker mixed humor with a sense of being an outcast.

“My mom made me feel good because she always called me big boned,” Walker said, then adding with a smile. “Kids at school called me chubby.”

With his stuttering problem, Walker was put in a special education class, increasing the belittling by classmates.

“My teacher put me in the corner and said I was special,” Walker said with a smile. “For four years I didn’t go out for recess. I was smart enough to know that I’d get beat up when I went out for recess.”

When Walker, one of seven children and raised in a Christian home, was in eighth grade, he was determined to change his status at school. He began reading out loud to overcome his stuttering and he started doing hundreds of pushups and situps a day to get fit. His efforts, which he says became obsessive, transformed him into the valedictorian of his high school senior class and the country’s top college football recruit.

“I had this anger in me from the putdowns as a kid,” Walker says. “I never felt I was good enough. This is going to freak you out. I told my mom the reason I started working out was because I wanted to break the necks of the people picking on me. I wanted to hurt them. I also said I didn’t want any teacher putting me down anymore.”

Talking to a room packed with 300 soldiers, Walker didn’t hide behind his trophies, or his accomplishments. He bared his soul, making it easier for the soldiers to ask for help. His point was simple. If a Heisman Trophy winner can ask for help, so can a soldier.

“For every individual out here who might be wrestling with an internal demon or a challenge, Herschel has shown them it’s okay to go get help for it,” said Col. Dr. Dallas Homas, the commander of the Madigan Army Medical Center at JBLM. “Not many of our sports heroes are as giving, as selfless, as Christian as he is. He’s a model for everyone to emulate.”

Walker, who wrote about his mental health issues in his 2008 book, Breaking Free, has shared his message of hope with more than 18,000 troops and has visited 51 military bases in the past five years. Since writing his book, Walker has been the spokesman for The Freedom Care Program, a mental health and addiction treatment program for the military.

Walker shares his revealing story to break down barriers for soldiers needing help.

“One of the things we combat in the military is the stigma that if you’re really strong you don’t have problems,” Homas said. “You certainly don’t reveal those problems to others. Every individual who might be wrestling with an internal demon or a challenge, Herschel has shown them it’s okay to go get help.”

While he filled headlines with his play in the NFL as he rushed for 8,225 yards, Walker painted for these listening soldiers a contrasting picture of a desperate man who was filled with rage and didn’t understand or fear pain. He talked of how he separated his shoulder in a game at the University of Georgia and insisted the trainer pop it in without a sedative. Off the field, Walker took unreasonable risks.

“I was this guy who used to love playing Russian Roulette,” Walker says. “People would say, ‘What do you want to do? Kill yourself?’ I’d say no. It was a game for me. Playing Russian Roulette showed how tough I was. I used to say to my ex-wife that I was going to kill her. Later, she told that me that I had said that, and I didn’t remember it.”

Walker said if he encourages one soldier to get help, then it’s been worth admitting and talking about his mental disorders.

“I tell people that one of the best things that ever happened to Herschel Walker isn’t winning the Heisman Trophy,” Walker says. “It was me going to the hospital. If I hadn’t gone to the hospital, I’d be dead today.”

Walker’s pivotal moment came a couple of years after he left the NFL when he nearly shot a delivery man. Angry about a late delivery, Walker got his hand gun and drove across town, set on killing the man. But as a furious Walker burst out of his car, he saw a bumper sticker on the delivery van. It read “Honk if you love Jesus.” That cooled Walker’s outrage.

“That’s when I realized I needed help,” Walker says.

Fortunately, his psychological hardships have drawn Walker closer to God, not driven him farther away. While the prosperity message is a common theme in sermons today, Walker said there’s no promise Christians won’t face hardships.

“I tell people all of the time just because you’re a Christian you’re not going to get a bed of roses,” Walker says. “You’ve got those thorns, too. Because you’re a Christian it can be very difficult for you. You have a cross to bear. It’s going to be tough.”

Walker, knowing that some of the soldiers he was talking to might have psychological problems stemming from post-traumatic stress disorder, tried to assure them that there was hope.

“We have the DNA of our Lord Jesus Christ,” Walker said. “You’re somebody. We all have problems. I finally saw that.”

This story was published in the Vol. 27, No. 4 issue of Sports Spectrum. Gail Wood is a freelance writer who worked as a sportswriter for newspapers for more than 30 years.